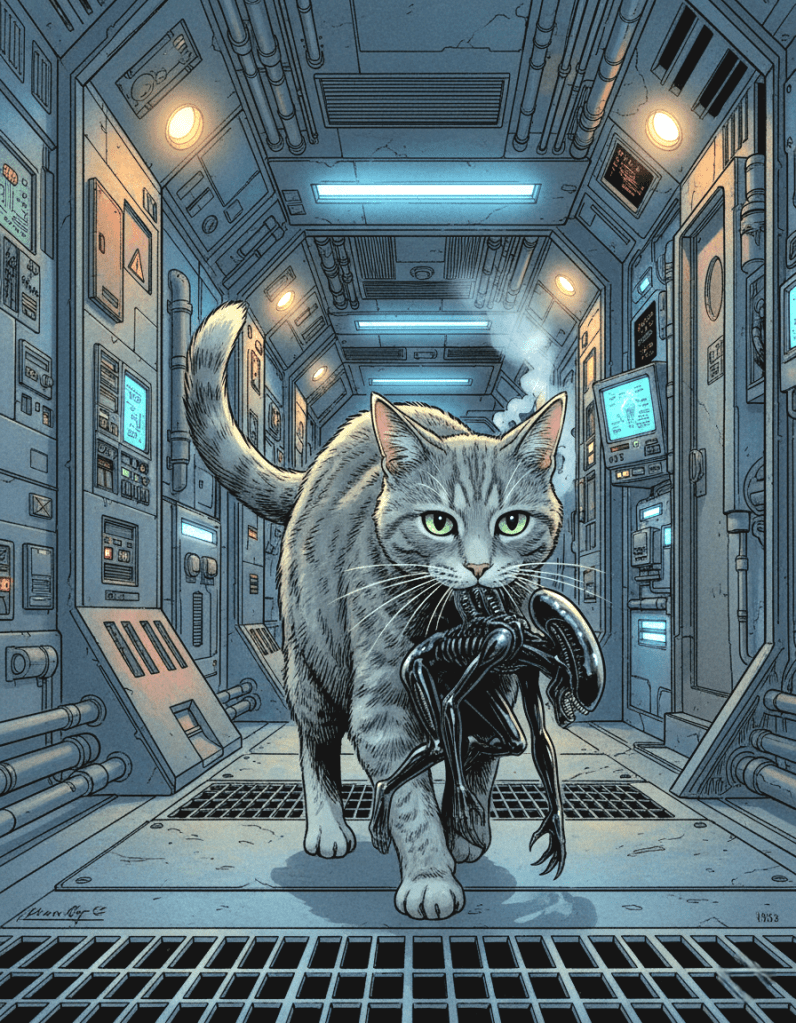

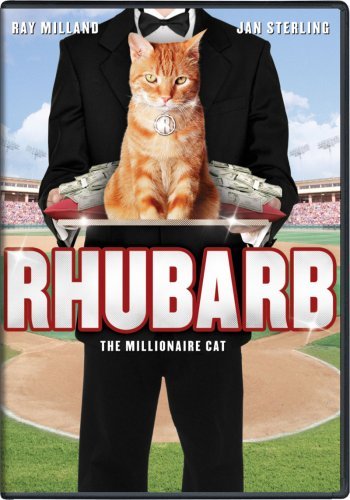

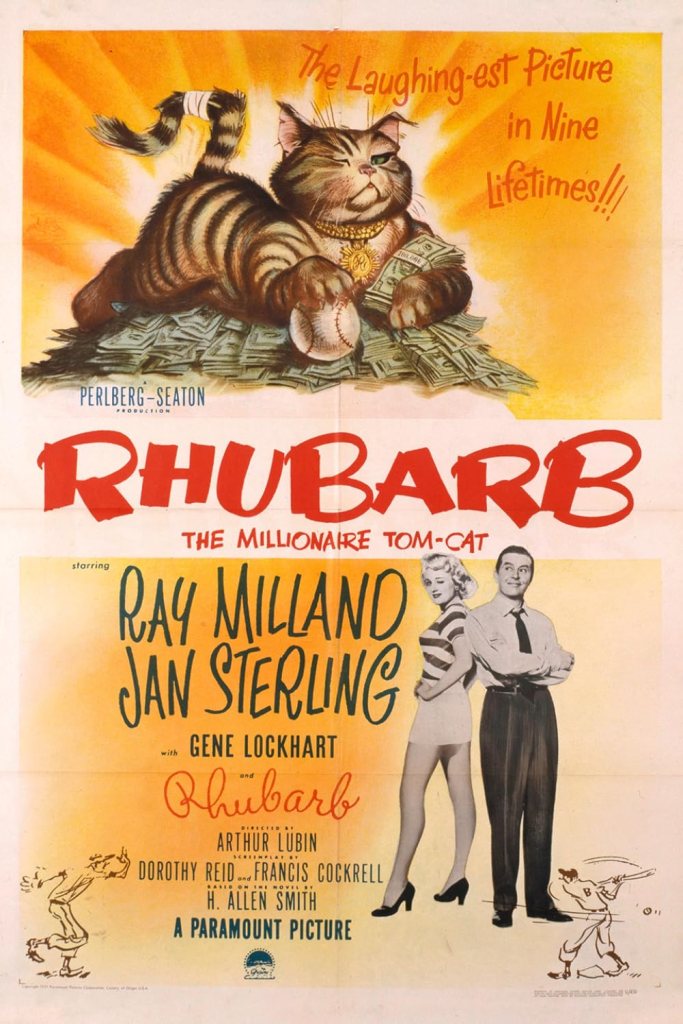

Orangey, the cat who famously belonged to Audrey Hepburn’s character in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, had an impressive and improbable film career beginning with 1951’s Rhubarb and ending with roles in TV series like Green Acres and The Flying Nun almost two decades later.

A new story in The Guardian charts Orangey’s film career and attempts to reconcile conflicting information about the famed feline. At least two cats played Orangey in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, while potentially dozens were used for Rhubarb, a comedy about a cat who inherits his wealthy late owner’s fortune and assets, including a baseball team.

“Watching the cat performances both within the movies and across the different titles certainly lends credence to the idea that Orangey was more a cat type, provided by trainer Frank Inn, than a specific animal,” The Guardian’s Jesse Hassenger writes.

In fact, color mattered less than resemblance because most of Orangey’s appearances were in black and white, so it’s possible Orangey wasn’t always Orange. (Later performances were filmed in color and some films were subsequently colorized.)

Using more than one cat for a role is pretty standard in Hollywood films that feature felines. Keanu, the 2016 Key and Peele comedy about an eponymous kitten who is stolen by drug dealers, cycled through several kittens as the pace of production was simply too slow compared to the rapid growth of real life kittens. In 2024’s A Quiet Place: Day One, two very similar-looking cats, Nico and Schnitzel, shared the role of Frodo, the cancer-stricken protagonist’s emotional support animal.

Why do people steal cats?

In early 2023, more than 50 cats in and around Kent, England, were abducted and returned with patches of fur shaved off.

At first people suspected the perpetrators were engaged in some bizarre form of animal cruelty — and some later copycats, for lack of a better word, across the UK may have been motivated to cause distress — but authorities later said they believe the catnappers were checking to see if the felines were spayed or neutered.

If they weren’t, those cats were kept for breeding, while the others were dropped off where they were found.

That rash of disappearances and other cases of car abductions factored into a staggering report from the Royal Kennel Club’s lost pets database: of the 25,000 pets reported missing in the UK between January 2023 and June 2024, more than 20,000 were cats.

Those cases and others are highlighted in a report from The Telegraph published on Thursday detailing the increase in reports of stolen felines. While the actual number of police reports are unknown due to discrepancies in the way such cases are classified by police, data from the Kennel Club and microchip companies, as well as anecdotes, indicate a concerning spike in cat theft even as the UK has mandated microchips for every pet cat.

Some, like the recent case involving an Amazon delivery driver, are crimes of opportunity. They’re spur-of-the-moment decisions by people who encounter cats they might want for themselves or people close to them.

Others, like the mass pet thefts in Kent, could have ties to larger organized crime operations.

And some are attempts to make a quick quid by petty thieves who count on the emotional bond between plpeople and their animals to demand ransom for the four legged family members, like one couple who abducted a woman’s cat and ransomed her for the equivalent of a few hundred dollars.

That woman, who was identified only by the pseudonym Helen in the story, said she was torn between getting her cat back and encouraging the people who took him.

“I was worried the same thing would just keep happening,” she told the newspaper. “It’s not something you want to encourage – paying to get your cat back – in case they do it again.”