Despite an arrest, a criminal charge hanging over her head and widespread scorn from locals, a delivery driver has “refused to speak about” what she did with a Charleston family’s cat after allegedly stealing the Calico.

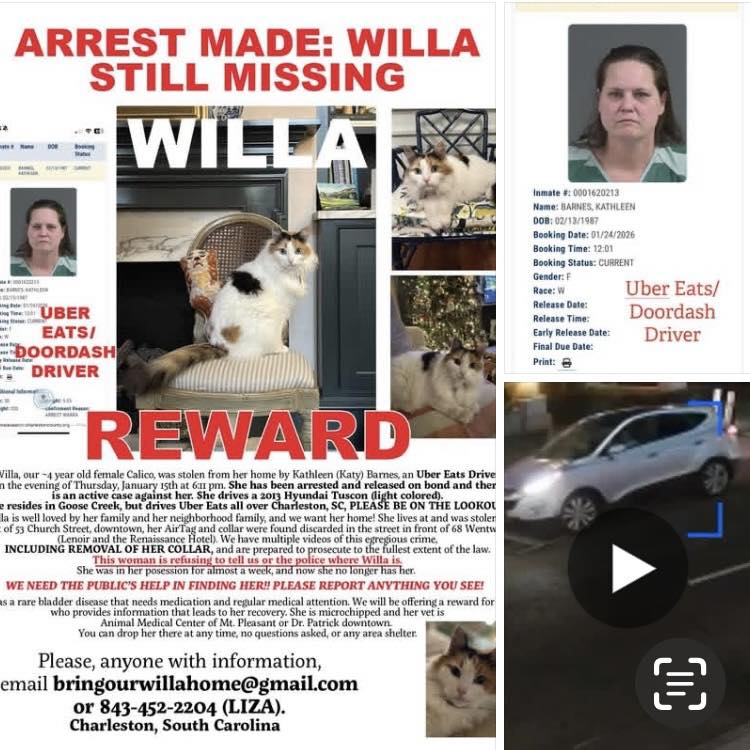

A story in Charleston’s Post and Courier details the herculean efforts by a family to get their cat back after 38-year-old Kathleen “Katy” Barnes allegedly stole the feline on Jan. 15, shortly after receiving a $15 tip for delivering Greek food on the same street.

When the Layfield family returned home that day, four-year-old Willa was nowhere to be found. The Layfields checked their security camera footage, which last showed Willa about 45 minutes before the family returned home but did not show her disappearance.

Since the extent of Willa’s outdoor activities involved straying no further than a few feet from the home, and mostly consisted of her sitting on the family’s front porch, the Layfields were worried and went to bed for an “uneasy” and “restless night,” per the Post Courier. When Willa’s AirTag pinged at 4 am near the Lindy Renaissance hotel about a mile away, Daniel Layfield got out of bed and rushed to the location. The device had been tossed in the street along with Willa’s collar.

The family has been relentless in tracking down information about Willa’s disappearance and getting access to surveillance camera footage from neighbors and local businesses, which is how they found footage of Barnes allegedly taking Willa (spotted on a neighbor’s cameras), then additional footage of her SUV stopping in front of the Lindy Renaissance hotel.

In video the Layfields pulled from a nearby gym’s surveillance cameras, Willa is seen on the dash of Barnes’ silver SUV. Barnes grabs her, removes the collar and AirTag, and tosses both out of the car before driving off again.

The Layfield family has also appealed to Barnes through statements to the press.

“Please let us know where she is,” Daniel Layfield said per the Post Courier, “if you have any compassion for animals and people.”

Charleston police deserve credit for taking the case seriously, going above and beyond what most departments would do in similar cases. They were able to secure a warrant to search Barnes’ home in Goose Creek, SC, but did not find Willa.

And this week they arrested Barnes for a second time, charging her with littering for disposing of Willa’s collar and AirTag, according to the Post-Courier.

It was the second time in about a week that police kept Barnes in overnight lockup, likely to send a message that they will not forget about the case. The Layfields have also enlisted the help of people who live in Barnes’ Goose Creek neighborhood, asking them to keep a lockout for the Calico, who has distinct markings.

This case is reminiscent of the theft of Feefee, a cat belonging to the Ishak family of Everett, Washington. Fefee was taken in the summer of 2024 by an Amazon Flex driver, and like the Layfields, the Ishaks had solid footage they were able to provide to the police, which led them to identify and track down the woman who took their cat.

That woman also refused to cooperate with police or tell the family what she did with their cat, despite their pleas and assurances that they weren’t interested in anything other than getting Feefee back.

Like the Layfield family, the Ishak family’s cat was well loved by the entire family, especially the kids, so Ray Ishak took the next several days off work and began driving around in an increasing radius, looking for the vehicle the Amazon contractor had been driving in the footage.

He found Feefee a few days later, scared and cowering in the bushes near the driver’s apartment. The driver had allegedly dumped the cat instead of returning her to the family, despite initially agreeing to bring her to the local police department.

In both cases, the families did everything right in their efforts to recover their four-legged family members.

They posted to social media, posted flyers, rallied support, and asked others to help spread the word. They reached out to local media, sent copies of the footage, then made themselves available for interviews and to plead for the return of their cats.

They also filed reports with the police and complained to the corporations — Amazon in the Washington case and Uber in the South Carolina case.

While Amazon is notoriously slow to respond to incidents like this and has repeatedly infuriated victims by treating the thefts as customer service issues, Uber said it contacted the driver and tried to persuade her to hand over the cat. While Barnes can’t technically be fired, as she’s a gig worker, the company said she will no longer be allowed to contract for Uber Eats.

“What’s been reported by the Layfields is extremely concerning,” Uber’s team wrote. “We removed the driver’s access to the Uber app and are working with law enforcement to support their investigation. We hope Willa is safe and reunited with her family.”

Unfortunately Willa’s been missing for two weeks now, and like most of the US, the normally temperate Charleston has been in a deep freeze, with temperatures plummeting below zero.

Because South Carolina views pets as property, as many states do, the worth of Willa’s life is pegged at a few hundred dollars at most, and she’s treated in the eyes of the law as an object.

That means the most severe charge the police could arrest Barnes for is petty larceny, a misdemeanor that carries a penalty of up to 30 days in county jail and a fine, if she’s convicted.

It is important to note that despite the footage, the charges are an allegation, and Barnes remains legally innocent pending a possible conviction.

But because the charge is just a misdemeanor, there is no pressure for her to cooperate and help the family get Willa back. (Or return her, if she still has the cat in her possession.)

Historically, pet theft has been associated with two primary motivations: thieves target breed cats and dogs because they believe they can make easy money selling them, whole others use stolen pets as bait or “training” for the violently conditioned dogs used in dogfighting. Some also target pedrigree pets to breed them.

In both these cases, and others that have been in the news recently, the thefts were crimes of opportunity, not pre-planned, and the cats were moggies. In addition, the cats were spayed/neutered. That rules out monetary gain by reselling or breeding. It also stretches credibility to believe gig workers are somehow more likely to be involved in dog fighting.

This is something new, a category of theft that may have began in earnest during the COVID era, when people felt isolated and shelters were literally being emptied due to the dramatic uptick in adoptions. Unable to find a companion animal through normal channels, some people stole pets for themselves.

But the shortage was short-lived, shelters and rescues are back in the familiar situation of having too many animals, and there’s no impediment to someone simply adopting a cat or dog instead of inflicting trauma on the animal and its family.

We hope the Layfields receive good news soon, and Willa is returned to the warmth and love she’s known with them.