Cats have taken over the internet, claim a mighty share of the $64 billion Americans spent on pet food in 2023, and have essentially installed themselves as the leisurely masters of 28 percent of American homes.

But it wasn’t always that way, and a look at the first-ever edition of Webster’s Dictionary reveals a very different attitude toward our furry overlords:

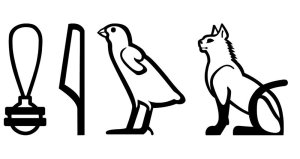

“The domestic cat needs no description. It is a deceitful animal, and when enraged, extremely spiteful. It is kept in houses, chiefly for the purpose of catching rats and mice.”

Wow. Whoever does feline PR should get a raise, because we’ve gone from “We tolerate the imperious little bastards because they’re good at killing rodents” to “Does my little angel want a snack? How about some ‘nip then? Anything for my bestest little pal!” in the span of two centuries.

Noah Webster, whose name is now synonymous with dictionaries, saw the effort to standardize spelling and pronunciation as central to formalizing an American linguistic identity distinct from our mother country. Or, as he put it, “[t]o diffuse an uniformity and purity of language in America” that would not only differentiate our English from England’s, but also unify the states at a time when many people still viewed the idea of a united states with skepticism.

By doing so, he hoped America would avoid the pitfall of dividing itself into regions of nearly mutually unintelligible dialects, a problem that plagues other countries. Consider the fact that India has almost 800 distinct languages and dialects, down from a staggering 1,652 in 1961 as hundreds of local languages died with the last generations of their speakers. Hindu, the country’s most popular language, is spoken only by about 43 percent of the population.

The goal, Webster wrote when he published his dictionary’s first edition, was “to furnish a standard of our vernacular tongue, which we shall not be ashamed to bequeath to three hundred millions of people, who are destined to occupy, and I hope, to adorn the vast territory within our jurisdiction.”

As dictionary.com notes, Webster wrote that passage in 1828 when the US population was just 13 million and vast swaths of what we now consider familiar territory was at the time largely unexplored wilderness.

His prediction of an America of 300 million people came true in 2006. Today there are approximately 335 million of us.

In other words, a hell of a lot has changed since the Connecticut born-and-raised Webster cobbled together a uniquely American system of spelling and pronunciation, so maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that attitudes toward cats have shifted so dramatically.

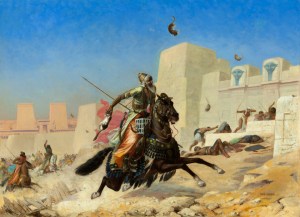

Still, we’d love to see the look on Webster’s face if we could bring him forward in time and show him how the “deceitful” and “extremely spiteful” little furballs have come to such prominence in American culture. What would Webster make of the spoiled modern house cat, with her condos, tunnels, toys, harnesses, bowls filled with salmon and duck, and even psychoactive recreational drugs for their enjoyment?

Bow before your feline overlords, Webster!