Homo sapiens are an invasive species who do irreparable harm to the environment and other animals on an unprecedented scale, a new study by the Feline Science Institute has found.

The results prompted feline scientists to add homo sapiens, commonly known as humans, to a database of destructive and invasive animals maintained by the Academy of Scientific Studies.

Cat scientists have only just glimpsed the breadth of human-initiated impact on other animals, Dr. Oreo P. Yums, lead author of the newest research paper, told reporters.

“We found humans are astonishingly, almost indescribably destructive,” Yums said. “For instance, although they fret about birds, humans kill more than a billion of them a year just with their skyscrapers, which birds are prone to fly into due to their mirrored surfaces. Add in wind turbines, cell towers, power lines, habitat loss and slow die-offs due to chemicals, and by conservative estimates we’re talking about billions of birds killed by humans every year without even tallying active measures like hunting.”

Humans have killed off an estimated 70 percent of the world’s wildlife in the last 50 years alone and show no sign of stopping. Oceans are overfished, animals like pangolins and big cats are ruthlessly hunted to extinction to feed demand within the Chinese traditional medicine market, and human addiction to palm oil means the “two-legged demon monsters don’t even have sympathy for their fellow primates,” mewologist Charles Clawin said.

“In Borneo and Sumatra there are entire schools, filled to capacity, for critically endangered orangutan babies who were orphaned by human contractors clearing ancient jungles to make room for more palm oil plantations,” he said. “Often, the humans use industrial equipment to tear down trees while the orangutans are still in them. Other times, they dispatch the mothers with pistols, not realizing there are babies clinging to them.”

In Africa, where the elephant population has plummeted in the last century, more than 110,000 elephants have been slaughtered in the past 10 years alone for their tusks. The elongated incisors are used to make jewelry and piano keys, and items made from ivory have become a status symbol in China, where growing middle and upper classes seek to show off their wealth with luxuries.

In 2019, Chinese businesswoman Yang Felan, dubbed the “Ivory Queen,” was arrested and charged with smuggling $2.5 million worth of tusks from Tanzania to her home country. Yang, “a key link between poachers in East Africa and buyers in China for more than a decade,” was a respected businesswoman, investor, restaurateur and vice chairwoman of the China-Africa Business Council.

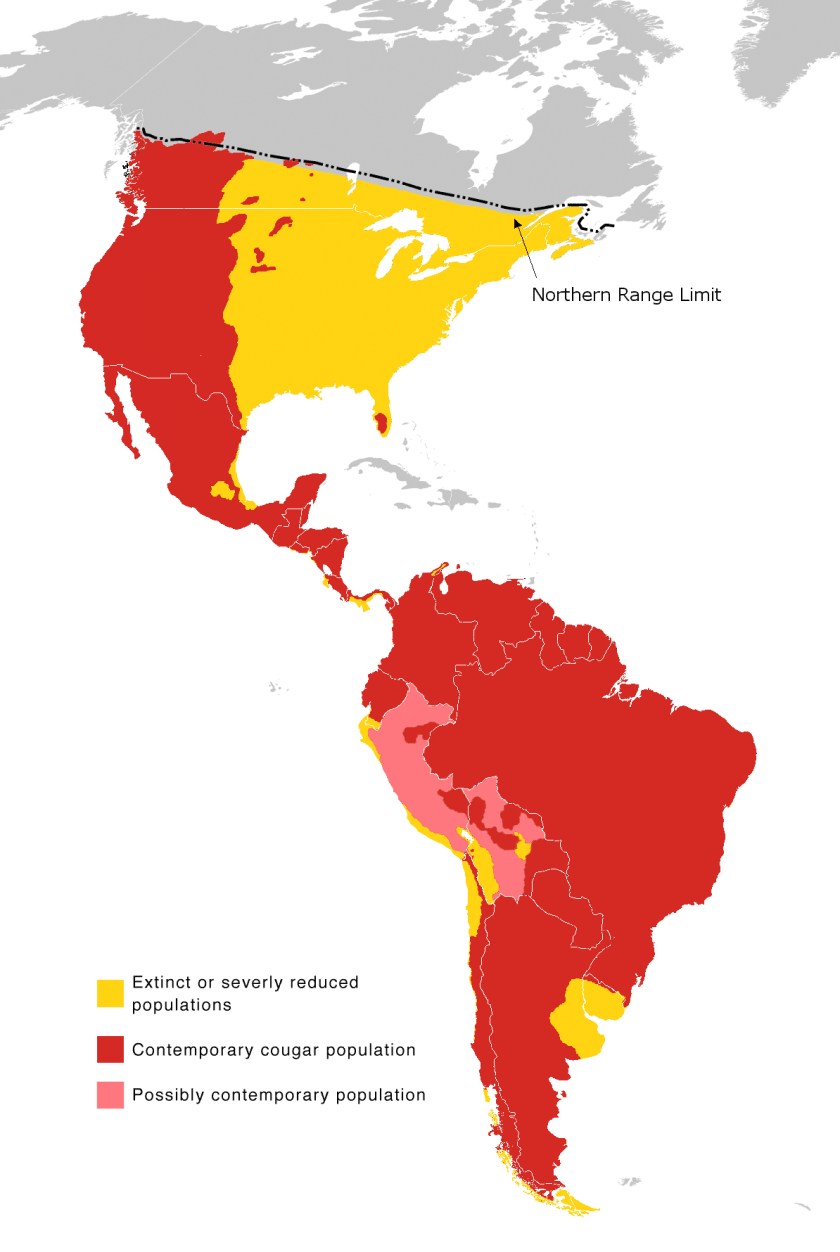

“Poachers continue to slaughter elephants and our big cat brothers and sisters,” said Luna Meowson, who tracks the illegal wildlife market for the University of Nappington. “Having extirpated tigers from virtually their entire range, poachers are turning to South America, where jaguar poaching increased 200 fold between 2015 and 2020. It never stops.”

Although the earliest details remain murky, fossil records show Homo sapiens first emerged in Africa about 200,000 years ago. The invasive species, which has a gestation period of about nine months, began rapidly breeding and immediately went to war with fellow members of the genus Homo.

After wiping out two-legged rivals including Homo neanderthalensis, Homo altaiensis, Homo denisova and Homo bodoensis, the victorious Homo sapiens set their eyes on other species. Throughout their history they’ve also proven remarkably adept at murdering themselves and continue to hone their skills.

“Those OG humans, they had to really work at slaughtering other species and extirpating wildlife,” said Chonkmatic the Magnificent, King of North American cats. “They didn’t have attack helicopters, stealth bombers, tanks, carrier battle groups, daisy cutters, artillery, mortars, phosphorous, napalm, biological weapons, or even small arms like rifles. In those days a pimply kid from Oklahoma sitting in an air-conditioned base in Virginia couldn’t wipe out an entire city 5,000 miles away by pressing a button ordering a drone to drop a nuke. They had to put some sweat into violence, you know?”

The species, known for its aptitude for tool-making in addition to eating ultra-processed foods and staring at screens, began with simple tools of destruction like the Mark I Spear, early bows and even torches. Over the centuries they innovated, coming up with clever and inventive new ways to inflict pain and end life until the advent of electricity, the industrial era and the brutally destructive war machines of modern times.

Human scientists have tried to obscure their species’ impact on wildlife and the planet by declaring species like felis catus “invasive” and “alien,” but even if cats are “guilty of grabbing a forbidden snack every now and then,” they don’t have the coordination, technology or will to carve up habitats, render entire swaths of the Earth uninhabitable with nuclear fallout, create Everest-size mountains of garbage, or effortlessly drive millions of species to extinction, Clawin said.

“They’re so good at it, they don’t even have to try,” he noted, pointing out human accidents or incidents of negligence like oil spills and chemical run-off into rivers. “We tend to think of humans out there with shotguns and rifles, cackling maniacally as they shoot anything that moves. And, sure, they do that, especially in places like Texas where the sight of any animal always prompts the question ‘Should we shoot it?’ But our research shows they can wipe out entire categories of fauna in their sleep. It’s remarkable.”

Additional reading: Polish institute classifies cats as alien invasive species