A woman who was found dead on a hiking trail may have been killed by a mountain lion, state authorities say.

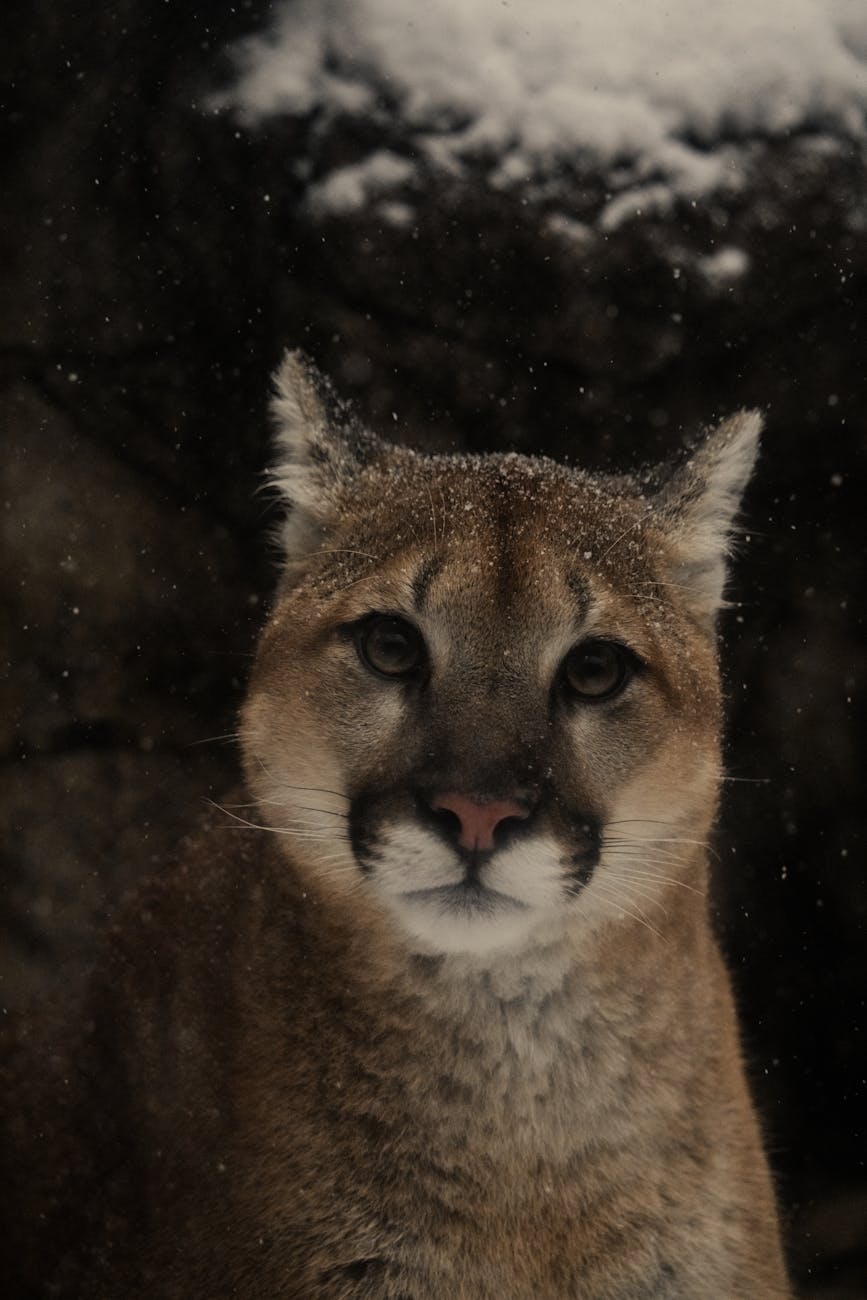

Several hikers were making their way along the Crosier Mountain Trail in northern Colorado at noon on Thursday when they came upon a woman laying on the ground and a puma about 100 yards away from her, according to police.

The hikers made noise and tossed rocks to scare the cat off, then one of them — a medical doctor — checked the woman and found no vital signs.

They notified authorities, who launched a massive search by air and ground, closing down the neighboring trails and bringing search dogs into the effort.

The search teams found and killed two mountain lions, who will be autopsied to determine if either had human remains in their stomachs. If they do not, rangers and police will keep looking, as they say Colorado law requires them to euthanize animals who have killed humans, local news reports said.

It’s important to note that there are no autopsy reports so far. Police don’t know how the woman died, if she was killed by the puma spotted near her, or if the animal approached after her death.

If an investigation does determine a puma was responsible, it’s crucial to place the incident in context. The last recorded fatal mountain lion attack in Colorado was in 1999, and was not confirmed. The victim, a three-year-old boy named Jaryd Atadero, wandered away from the hiking group he was with and was never seen again.

Search efforts in the following days and weeks didn’t turn up anything, but in 2003 another group of hikers found part of Atadero’s clothing. His partial remains were later found nearby.

Police said Atadero could have been killed by a mountain lion, but there’s no definitive evidence and his cause of death remains a mystery.

Aside from that incident, there have been 11 recorded, non-fatal injuries attributed to pumas in Colorado in the past 45 years despite as many as 5,000 of the wildcats living in the state’s wilderness.

Nationally there is some discrepancy in record-keeping, but most sources agree there have been 29 people killed by mountain lions in the US since 1868. By contrast, more than 45,000 Americans are killed in gun-related incidents per year, about 40,000 Americans are killed in traffic collisions annually, and between 40 and 50 American lives are claimed by dogs per year.

Americans are a thousand times more likely to be killed by lightning than by a puma, according to the US Forestry Service.

Cougars are elusive, do not consider humans prey, and the vast majority of the time go out of their way to avoid humans. Most incidents of conflict are triggered by people knowingly or unknowingly threatening puma cubs, or cornering the shy cats.

Despite that, there’s confusion among the general public. Mountain lions are routinely confused with African lions, so some Americans believe they are aggressive and dangerous.

Pumas, known scientifically as puma concolor, are part of the subfamily felidae, not pantherinae, which means they are more closely related to house cats and smaller wildcats than they are to true big cats like lions, tigers, jaguars and leopards.

Pumas can meow and purr, but they cannot roar. Their most distinctive vocalization is the powerful “wildcat scream,” leading to nicknames like screamer.

In the Colorado case, police say they believe the victim was hiking alone. Her name hasn’t been released, likely because authorities need to notify next of kin before making her identity public.

This is a tragedy for the victim and her family, and we don’t wish her fate on anyone. At the same time, we hope cooler heads prevail and this incident does not spark retaliatory killings or misguided attempts to cull the species.