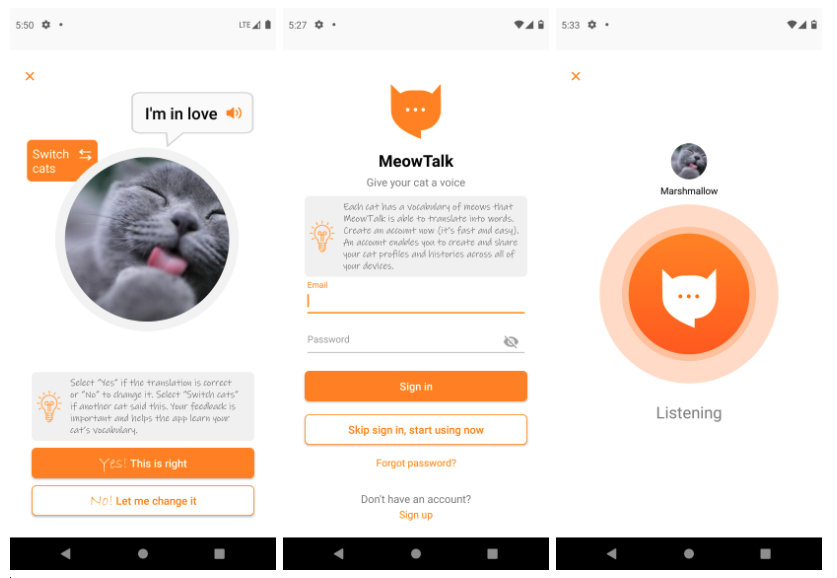

A few years ago when MeowTalk made a minor splash in the startup world, I was pretty bullish on its potential to help us understand our cats better.

Sure, the app had an unhelpful habit of attributing improbably loving declarations to Buddy, but I thought it would follow the trajectory of other machine learning models and drastically improve as it accumulated more data.

More users meant the app would record and analyze more meows, chirps and trills, meaning it was just a matter of time before the AI would be able to distinguish between an “I want attention!” meow and a “My bowl is dangerously close to empty!” meow.

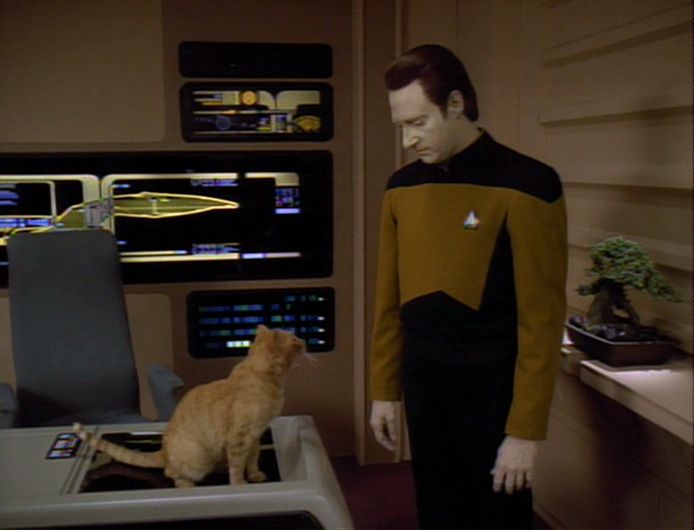

Obviously that didn’t happen, and what I personally didn’t take into account back then — and should have, given how obvious it is in retrospect — is that cats don’t just communicate via vocalizations.

In fact, cats don’t normally incorporate vocalizations into communication at all. Pet kitties do it entirely for our benefit because they know we’re generally awful at interpreting body language and we are completely useless when it comes to olfactory information.

It’s actually amazing when you really think about how much of the heavy lifting cats do in our efforts to communicate with each other. They recognize we can’t communicate the way they do naturally, so they try to relate to us on our terms. In return, we meet them less than halfway.

No wonder Buddy sometimes looks frustrated as he meows at me, as if I’m the biggest moron in the world for not understanding the very obvious thing he’s trying to tell me.

Now the Chinese tech giant Baidu is throwing its hat into the ring after filing a patent in China for an AI system that uses machine learning to decode animal communication and “translate” it to human language.

Machines are designed to process things from a human viewpoint according to human logic, so if Baidu wants to succeed where MeowTalk has not, its engineers will need to take a thoughtful approach with the help of animal behavior experts.

This is a hard problem that encompasses animal cognition, neuroscience, linguistics, biology, biochemistry and even philosophy. If they approach this strictly as a tech challenge, they’ll set themselves up for failure.

Without the information and context clues provided by tails, whiskers, facial expressions, posture, eye dilation, heart rate, pheromones and even fur, an AI system is only getting a fraction of the information cats are trying to convey.

Trying to glean meaning from that is like trying to read a book in which only every fourth or fifth letter is legible. There’s just too much missing information.

Even if we can train machines to analyze sound visual, tactile and olfactory information, it may not be possible to truly translate what our cats are saying to us. We may have to settle for approximations. We’ve only begun to guess at how the world is interpreted differently among human beings thanks to things like qualia and neurodivergence, and the way cats and dogs see the world is undoubtedly more strange to us than the way a neurodivergent person might make sense of reality.

“He grimaced. He had drawn a greedy old character, a tough old male whose mind was full of slobbering thoughts of food, veritable oceans full of half-spoiled fish. Father Moontree had once said that he burped cod liver oil for weeks after drawing that particular glutton, so strongly had the telepathic image of fish impressed itself upon his mind. Yet the glutton was a glutton for danger as well as for fish. He had killed sixty-three Dragons, more than any other Partner in the service, and was quite literally worth his weight in gold.” – Cordwainer Smith, The Game of Rat and Dragon

An animal’s interpretation of reality may be so psychologically alien that most of its communication may be apples to oranges at best. Which is why I always loved Cordwainer Smith’s description of the feline mind as experienced via a technology that allows humans with special talents to share thoughts with cats in his classic short story, The Game of Rat and Dragon.

An animal’s interpretation of reality may be so psychologically alien that most of its communication may be apples to oranges at best. Which is why I always loved Cordwainer Smith’s description of the feline mind as experienced via a technology that allows humans with special talents to share thoughts with cats in his classic short story, The Game of Rat and Dragon.

In the story, humans are a starfaring civilization and encounter a threat in the void between stars that people don’t have the reaction speed to deal with. Cats, however, are fast and swift enough, and with a neural bridge device, teams of humans paired with cats are able to keep passengers safe on interstellar journeys.

The narrator, who is one of the few people with an affinity for teaming up with felines, hopes he’ll be paired with one of his two favorite cats for his latest mission, but instead he’s assigned to partner with an old glutton of a tomcat whose mind was dominated by “slobbering thoughts of food, veritable oceans of half-spoiled fish.”

The narrator wryly notes that the last time one of his colleagues was paired with that particular cat, his burps tasted of fish for weeks afterward. But the cat in question, despite being obsessed with fish, is a badass at killing “dragons,” the human nickname for the bizarre entities that attack human ships in space. (The software that allows felines and humans to link thoughts also portrays the “dragons” as rodents in the minds of the cats, stimulating their ancient predatory drive so they’ll attack instantly when they see the enemy.)

We can’t know for sure if Smith’s interpretation of the feline mind is accurate, but another part rang true when he wrote that cat thoughts were all about the moment, filled with sentiments of warmth and affection, while they rapidly lost interest in thoughts about human concerns, dismissing them “as so much rubbish.”

If the mind of a cat is that relatable, we’ll be incredibly lucky. But in reality we’re dealing with animals who evolved in drastically different ecological niches, with different priorities, motivations, and ways of looking at the world — literally and figuratively.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to understand our furry friends. Research has yielded interesting information about the way animals like whales and elephants communicate, and AI is at its best when it augments human creativity and curiosity instead of trying to replace it.

Even if we don’t end up with a way to glean 1:1 translations, the prospect of improving our understanding of animal minds is tantalizing enough. We just need to make sure we’re listening to everything they’re saying, not just the meows.