It’s too bad cats can’t swear.

While kittens don’t often have problems finding homes due to their overwhelming cuteness and antics, it usually takes a sad story to drum up considerable interest when an adult feline is up for adoption.

As the SPCA of Niagara learned, talkative parrots, especially birds who can swear up a storm, have their pick of homes.

In June, a potty-mouthed parrot named Pepper was surrendered to the shelter, and when the SPCA put the call out — specifying they’d prefer someone with experience caring for birds and a sense of humor — the applications kept rolling in, totaling more than 400.

“His famous line is ‘Do you want me to kick your ass?'” a shelter employee said in an interview last month shortly after announcing Pepper was up for adoption.

Shelter staff asked applicants to include photos of their bird enclosures in addition to the usual pre-adoption questions, eventually narrowing the Pepper Sweepstakes down to 10 potential homes.

This past week, Pepper was finally taken to his new abode in Olean, a small city in western New York. The couple who adopted him are not only experienced with birds, they know all about avian vulgarity. They have a parrot named Shelby who apparently “makes Pepper look like a saint.”

As for Pepper, it looks like he’s getting his bearings before heaping abuse on his new caretakers.

“He hasn’t cursed at them yet, but we know it’s coming,” shelter staff wrote in an update.

In recent decades, research has shown birds can be exceptionally intelligent. Crows, for example, use tools, can differentiate between human faces, and remember which humans have wronged them or treated them well.

While many people assumed parrots merely imitate human language, long term behavioral studies show the birds are able to use words in context and invent novel combinations of words. As with other animals, syntax remains elusive.

The most famous example was Alex the African Gray, who was the subject of research by animal cognition expert Dr. Irene Pepperberg. Alex, who died in 2007 at the age of 31, was able to count and could perform simple calculations. He was talkative, conversant and often told his caretakers how he was feeling, what he wanted, and what he thought of the tests they’d give him. (Like a child, Alex would try to get out of exercises he was bored with by asking for water, saying he was tired and wanted a nap, or just flubbing his answers.)

We are not above crude humor here at PITB, and in the past we’ve written about Ruby, our favorite talking parrot. Ruby lives in the UK with her owner, Nick Chapman, and the pair were among the very earliest Youtube stars thanks to videos of Ruby’s shockingly vulgar, extremely British tirades and Chapman’s infectious laugh.

Warning for those who are offended by bad language or are viewing at work: Ruby is known for liberal use of c-bombs-, t-bombs, f-bombs and just about every other linguistic bomb you can think of, in addition to British slang like “bollocks.” If that’s a problem for you, skip this video.

Eric the Legend, a parrot who lives in Australia, is also a favorite on Youtube for his habit of declaring himself “a fookin’ legend!“

We’re glad Pepper has found a home where his idiosyncratic nature will be cherished, and we hope the future will bring videos of Pepper and Shelby going back and forth. Parrots are social animals, after all, and what fun are insults if you’ve got no one to trade them with?

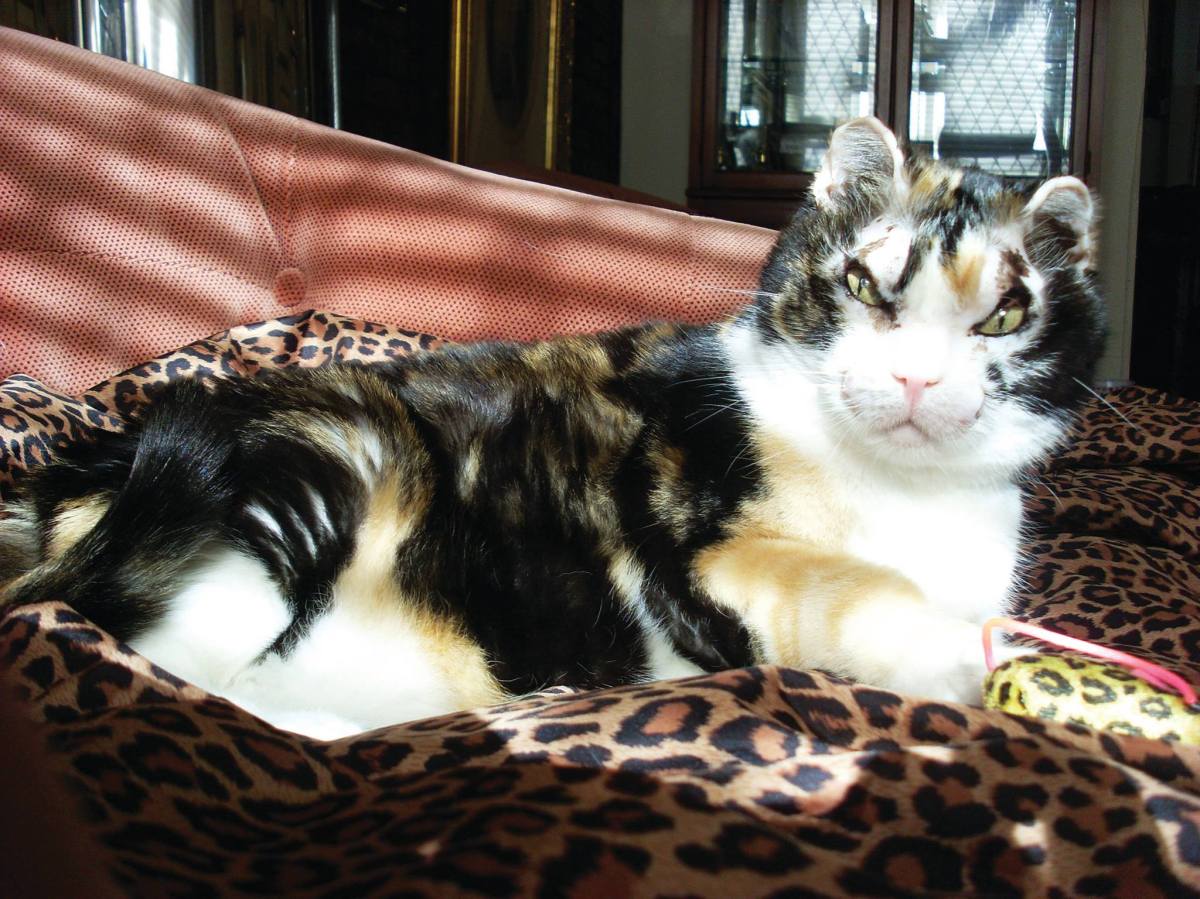

Top image of Pepper courtesy of Niagara SPCA.