A man in the UK has spent a small fortune on the possibility of reviving his dead cat.

Mark McAuliffe says he was so upset when his 23-year-old cat’s health began to fail that he made arrangements with a Swiss firm to preserve her body when she passed away.

The 38-year-old adopted Bonny, a domestic shorthair, while he was a teenager, and she’s been with him for more than half his life, including his entire adulthood.

Usually when stories like this make the news, they’re about people who preserve their cat or dog’s DNA for cloning.

That’s not what’s happening here.

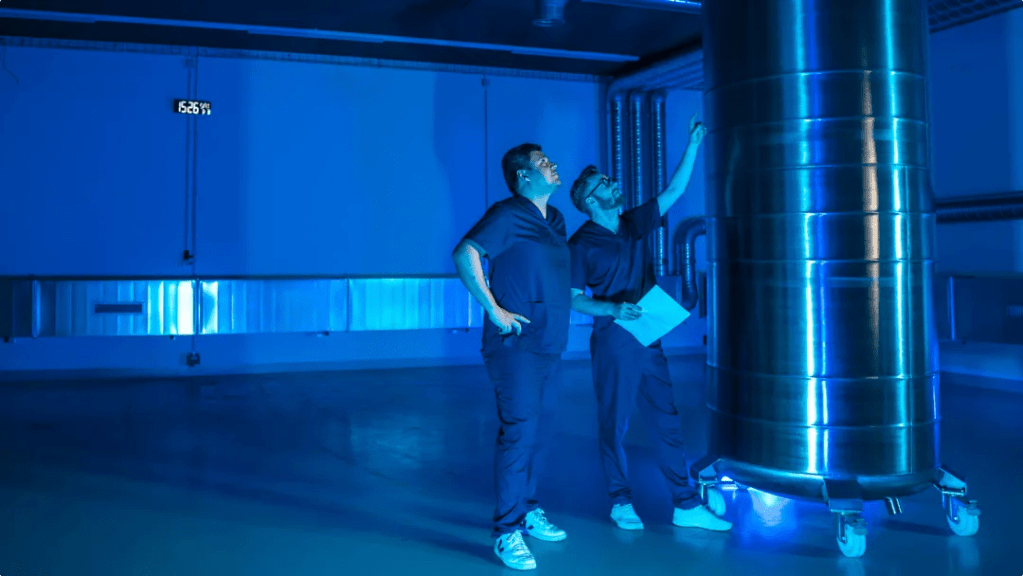

Bonny has been placed in a cryopreservation unit, which uses liquid nitrogen to freeze her entire body. Freezing a body essentially suspends it in time. Extremely cold temperatures — as close to absolute zero as possible — suspend cellular activity, including decay.

It’s called cryopreservation, and while the concept is most frequently invoked in science fiction, putting a body into cryostasis is real and within the technological capabilities of modern science.

The company McAuliffe paid to preserve his cat is Switzerland-based Tomorrow Bio, which is affiliated with the European Biostasis Foundation. The technology is used for several other purposes in the medical field, the food industry and in certain engineering applications.

McAuliffe is gambling on the future, or a version of it in which people and animals can be revived and repaired, like Lazarus in a lab. But it wouldn’t be much of a future for Bonny if her human wasn’t with her, so McAuliffe has reserved a spot for himself as well, hoping to meet her in better times.

“This cushioned the blow about Bonny’s death,” he said, “because I have got it in the back of my mind that it is not going to be the final goodbye.”

The European Biostasis Foundation runs the cryovaults where clients are kept. The organization told the Daily Mail that it has five “full body patients,” 15 preserved brains, two dogs and eight cats. In addition, more than 700 people have made arrangements to have their own bodies frozen upon death.

There is, of course, a hiccup.

While freezing a body is possible, thawing is not — not without destroying the body.

That’s because ice crystals form and rupture cell walls when the body is brought out of cryopreservation, no matter how slow the process.

The workaround involves using cryoprotectants, essentially a form of anti-freeze that would prevent the formation of damaging ice crystals despite the temperature.

That, however, introduces an entirely new set of problems, including the fact that cryoprotectant is toxic at the levels required for preservation.

Preserving the brain presents an entirely different set of problems, as our neurons and neural pathways begin to decay immediately after death. Our brain topology and neural connections are part of who we are, part of what makes our minds uniquely our own. Neuroscience and cryostasis technology each have a long way to go before scientists can even attempt to thaw a brain.

So by spending almost $22,000 to preserve Bony, and buying a plan to preserve himself (at a cost of $230,000), McAuliffe is banking on major breakthroughs in biology, as well as the ability to precisely control temperatures. To successfully thaw a body without destroying it, the entire body must be warmed at the same time, including all internal organs. That’s a significant technical challenge.

It’s also a gamble on the general shape of the future, placing hope that progress will continue. It assumes we won’t lapse into another dark age, that we won’t lose technology and expertise to devastating wars, plagues or other disasters that could set humanity back decades or centuries.

Finally, there’s a major hurdle that has little to do with science behind cryopreservation. It’s the simple fact that human lives are short, companies that promise centuries of operation can’t guarantee that outcome, and a lot can happen while a person sleeps away those years.

There’s a great short story by the Welsh science fiction novelist Alastair Reynolds about a wealthy man who wakes after centuries of cryosleep to find that the company who managed his crypt went bankrupt. From there it changed hands several times until it ended up in the portfolio of a corporate raider.

So the narrator, expecting to be woken to fanfare, deferential treatment and a bright technological future instead finds himself indebted and facing a reality much different and more depressing than he ever imagined.

I sympathize with McAuliffe, who obviously loves Bonny a great deal, and I see the appeal of becoming a refugee from the past, entering into a cryovault in the hope of emerging into a better future. But man, that’s a huge gamble.

In the meantime, there are plenty of cats who need homes and have a lot of love to give. Every shelter cat is a potential Buddy!