There’s a popular meme among Alien fans that depicts Jonesy the Cat walking nonchalantly down one of the starship Nostromo’s corridors with his tail up, carrying the corpse of the recently-spawned alien in his mouth like he’s about to present a dead mouse as a gift to his humans.

The joke is self-evident: if the crew of the Nostromo had allowed Jonesy to take care of business from the get-go, the alien would have been disposed of before it had the chance to grow into the monstrosity that haunted the decks of the Nostromo and the nightmares of viewers.

Of course then there’d be no movie. No ripples of shock in theaters across the US as audiences were confronted by something more nightmarish and utterly alien than popular culture had ever seen before. No indelible mark left on science fiction.

Despite the film’s retrofuturistic aesthetic, it’s difficult to believe Alien first hit theaters almost half a century ago.

That’s testament to director Ridley Scott working at the height of his powers, the carpenters, artists and set dressers who created the starship Nostromo’s claustrophobic interior, the design of the derelict starship where the alien was found, and the bizarre creature itself.

The alien ship and creature designs were the work of Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, who was little-known at the time but floored Scott and writer Dan O’Bannon with his hyper-detailed paintings of grotesque biomechanical scenes.

Giger’s work, specifically his 1976 painting Necronom IV, was the basis for the titular alien’s appearance. The alien, called a xenomorph in the film series, is vaguely androform while also animalistic. It is bipedal but with digitgrade feet and can crawl or run on all fours when the situation calls for it. It hides in vents, shafts and other dark spaces, coiling a prehensile tail that ends in a blade-like tip.

But it’s the creature’s head that is most nightmarish. It’s vaguely comma-shaped, eyeless and covered in a hard, armored carapace that ends just above a mouth full of sinister teeth like obsidian arrowheads. There’s perpetually slime-covered flesh that squelches when the creature moves but there are also veins or tendons or something fully exposed without skin, apparently made of metal and bone. Maybe those ducts feed nutrients and circulate blood to the brain. Maybe they help drain excess heat from the creature’s brain cavity.

Regardless, it’s a biomechanical nightmare that the Nostromo’s science officer, Ash, admiringly calls “the perfect organism” whose “structural perfection is matched only by its hostility.”

The alien, Ash declares, is “a survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

Part of what makes Jonesey so beloved is the fact that, together with the xenomorph and Ripley, he completes the triumvirate of survivors. We see Jonesy scurry into the protection of tiny confined spaces to escape the alien, hissing at it in the dark. We see him dart into the bowels of the ship after sensing the stalking creature, adding another blip to the crew’s trackers. Finally we see him settling into a cryosleep pod with Ripley, like so many other cats with their humans, when the threat has passed.

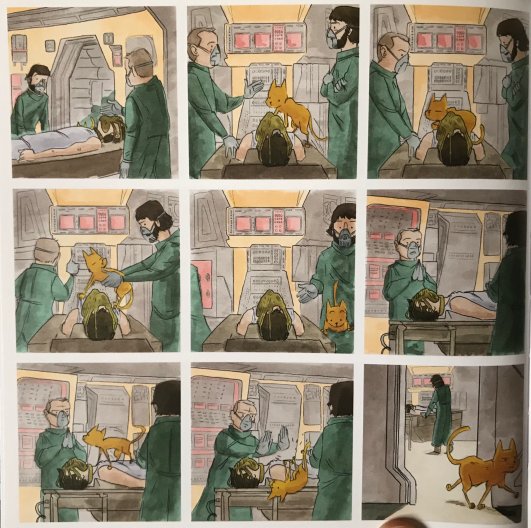

Jonesy — affectionately referred to as “you little shithead” by Ripley in the second film — appears in the franchise’s two most famous films, his own comic book series titled Jonesy: Nine Lives on the Nostromo, a 2014 novel (Alien: Out of the Shadows), and in hundreds of references in pop culture over the last half century, from appearances in video games (Halo, World of Warcraft, Fortnite) to references and homages in movies and television shows.

He’s like the anti-xenomorph. Cats are predators, after all, and Jonesy might be the xenomorph to the ship’s rodents just like every ship’s cat in thousands of years of human naval endeavors. But to the crew members Jonesy’s a source of comfort, a warm, furry friend to cuddle with. Unlike the xenomorph he’s got no biological programming urging him to impregnate other species with copies of himself in one of the most horrific gestation processes imaginable.

Xenos are like predators on steroids, gorging themselves on their victims to fuel unnaturally swift cell reproduction and growth. As a result, over the decades some have speculated that the alien simply ignored the cat, deeming its paltry caloric value unworthy of the effort to kill.

The idea that Jonesy was too small to interest the alien is proved a fallacy in later franchise canon when we see the aftermath of a xenomorph consuming a dog. It’s indiscriminate in its quest for energy, feasting on adult humans and animals alike until two or three days pass and it’s a 12-foot-tall, serpentine nightmare the color of the void of interstellar space.

Just imagine sitting in a theater in 1979. Your idea of science fiction is sleek jet-age spacecraft, Star Trek and Stanley Kubrick’s clinical orbital habitats from 2001: A Space Odyssey. You’re expecting astronauts, heroes, maybe a metal robot or an alien who looks human except for some funky eyebrows, green skin or distinct forehead ridges.

Instead you get a crew of seven weary deep space ore haulers inhabiting a worn, scuffed corporate transport ship, complaining about their bonuses and aching for home, family and the familiar tug of gravity.

But home will have to wait. The ship has logged an unusual signal of artificial origin broadcasting from a small planet in an unexplored star system. The crew has no choice but to investigate. It’s written into their contracts, which stipulate the crew will forfeit their wages if they disregard the signal.

So they land, suit up, move out and find a derelict starship. An incomprehensibly massive vessel so strange in detail and proportion that it could only have been built by an alien mind, with unknowable motivations and psychology.

Inside, hallways that look like ribcages lead to vast chambers with utterly bizarre, inscrutable machinery that seems to consist of biological material — skin, bone, joints, organs — fused with metal. In one of them the corpse of an alien, presumably a pilot, is integrated into a complex array. It’s at least twice the size of a large human man. Its elephantine head is thrown back in the agony of its last moment, when something exploded outward from its body, leaving a mangled ribcage, torn papery skin and desiccated organs.

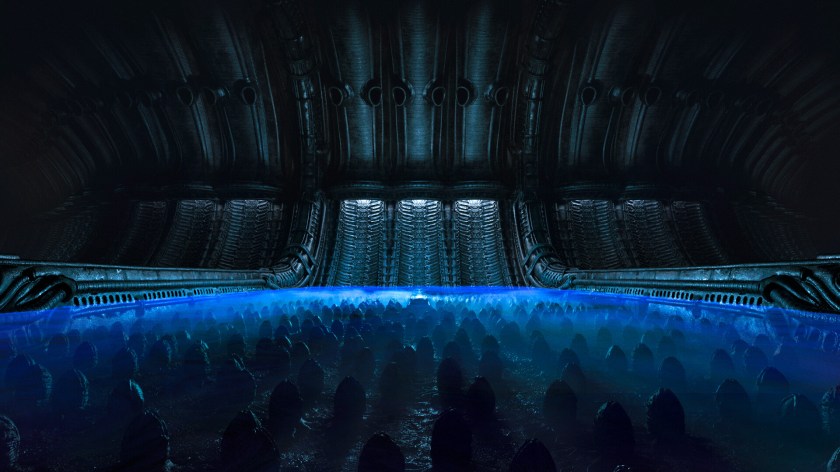

And beneath that, a shaft leading to another horror — a chamber that seems to stretch for kilometers in either direction, where leathery eggs are cradled in biomachinery and bathed in a bioluminescent cerulean mist.

The decision to enter that chamber sets off one of the most shocking scenes in cinema history, leads to the birth of pop culture’s most terrifying monster, and sent millions of theater-goers home with nightmares in the spring and summer of 1979.

It’s almost too much to handle. But take heart! The unlikely female protagonist makes it to the end, and so does the cat. What more can you ask for?