No one knew Saigon better than Katherine Lee Guard.

When he arrived at the wildlife ranch in Thermal, Calif., as a baby in the mid-90s, it was Guard who stayed up with him at night, bottle-feeding the orphan cub and swaddling him in soft blankets. She was by his side as he grew, tending to his needs, taking walks with him through the desert and scrubland on the compound that was his home.

Then one day the massive Amur tiger turned on her.

“It was just so shocking even though I knew it could happen,” Guard recalled. “I thought I knew but until it happened, I had no idea. It was terrifying and oddly a weird ‘How dare you!’ kind of feeling that came over me. Like ‘How dare you come at me after all I’ve done for you?’ Because I’d raised him, bottle fed him, been up all night with him.”

Guard was equally surprised by her own reaction, which she described as “more indignation than fear,” but it was that indignation that “allowed me to shelve my fear long enough to get away and out of the enclosure.” If Saigon had sensed her fear, his predatory instincts could have overridden the maternal affection he felt for her.

Saigon never tried to kill Guard. If he had, she wouldn’t be here to tell the story. He was merely warning her that he didn’t want her near him that day, and he made sure she got the message.

Amur tigers, also known as Siberian tigers, are the largest big cat subspecies in the world, topping out at 700 pounds, with males spanning 10 feet from nose to tail.

But the encounter — a growl, a much-less-than full strength swipe and a warning bump — was enough to turn Guard into “a nervous, vomiting wreck” once she extricated herself from the enclosure.

“Getting swatted by a paw, even with sheathed claws, hurts like hell,” Guard told PITB. “I’d feel trounced, disappointed and relieved at the same time. And stupid for being in there with them, although I never would have admitted that to anyone back then.”

That first bad encounter with Saigon, and similar encounters with a lion named Tsavo that Guard had also bottle-fed when he was a cub, planted seeds of doubt in her mind about what she was doing on that California ranch, working with a man who had previously used the big cats in circus performances.

Years earlier when Guard’s mom came to visit her, Guard came out to meet her with baby Saigon in her arms, feeding him from a bottle.

Her mother stopped and took in the scene. “That’s not the baby I imagined for you,” she said flatly.

“I never forgot it,” Guard said.

Later, while caring for a female Bengal named Bombay, Guard had an epiphany. Like so many others who make it their life’s work to be near big cats, she had always been beguiled by the beautiful, powerful and dangerous animals. Looking at Bombay, Guard realized the regal tiger was “totally without pretense,” moving with the purpose and grace of a being self-assured in her existence.

“She was purposeful and unyielding and for the first time I felt separate from her and it didn’t bother me,” Guard said. “It was beautiful to realize that she didn’t need me or anyone else. Had she been given a chance in the wild, she would have flourished. The desire to know her thoughts and be her friend lessened in me because I started to appreciate her for her, not for how she could make me feel. ‘She’s not existing for me! She exists for herself!’ We don’t ‘own’ Bombay. Bombay ‘owns’ herself.”

“It was a light bulb moment, and in hindsight I think it was the beginning of the change in my mindset.”

Guard stopped the practice of going “full contact” with the big cats — meaning caring for them without any barriers or safety measures in place, relying on luck to avoid death or dismemberment — and eventually left the ranch around 2003.

In the two decades since, she’s been focused on educating the public about big cats, supporting conservation efforts and trying to rescue the unfortunate tigers, lions, jaguars, leopards and other wild felids who have the misfortune of living in roadside zoos where they’re sedated and exploited for customer selfies, or living sedentary, unnatural lives in cramped backyards in states like Texas and Florida.

Like many others who have dedicated their lives to helping those animals, Guard is encouraged by the 2022 passage of the Big Cat Public Safety Act — but also miffed that it took lawmakers so long, and worried that loopholes in the law will be exploited by people determined to “own” Earth’s endangered apex predators.

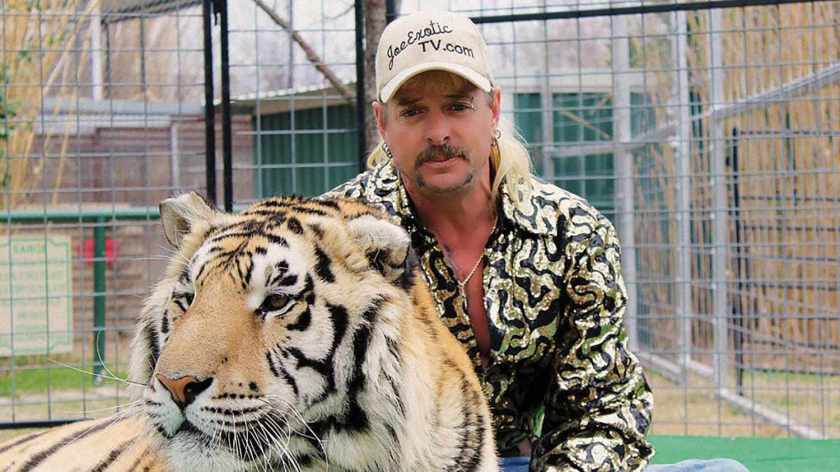

The world of big cat handling is a small one, and the people in that world tend to know each other if not always well, then by reputation or in passing. Guard remembers meeting Joe Exotic, the “star” of the infamous Netflix documentary Tiger King, in the late 1990s. Her boss and mentor at the time, Wayne Regan, wanted Exotic to surrender some of his cats to the sanctuary. Regan and Guard had seen “Exotic’s” handiwork up close when they examined some of the tigers another sanctuary had managed to wrangle out of his care. The tigers were stressed, suffered from poor nutrition and were not well cared-for.

Exotic came to the meeting with a sickly, malnourished lion cub as if taunting the pair.

“I hated him immediately,” Guard said.

She was overcome with a desire to “steal the poor malnourished cub he had with him,” but Regan cautioned her against it. Knowing what “Exotic” — real name Joseph Allen Maldonado — is capable of, it’s probably a blessing that she didn’t, but she still thinks of the cub all these years later.

Exotic remains in a federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas, where he’s serving a 21-year sentence after he was convicted of two counts of trying to hire a hitman to kill his arch-nemesis, big cat sanctuary operator Carole Baskin. He was also convicted of 17 counts of animal abuse, and his name is synonymous with the horror and suffering big cats endure when they’re in the possession of private “owners” and roadside zoo operators.

Big cat advocates lament the fact that the documentary, as popular as it was, spent more time focusing on Maldonado’s eccentricities, Machiavellian maneuvering and manipulation of people in his orbit than it did on the suffering of the animals in his “care,” but it did draw attention to his crimes and the plight of tigers in the US.

“He tortured and killed and exploited so many animals,” Guard told PITB. “He is a coward piece of shit who is right where he should be. He is no ‘Tiger King’ and never should have had a minute of fame.”

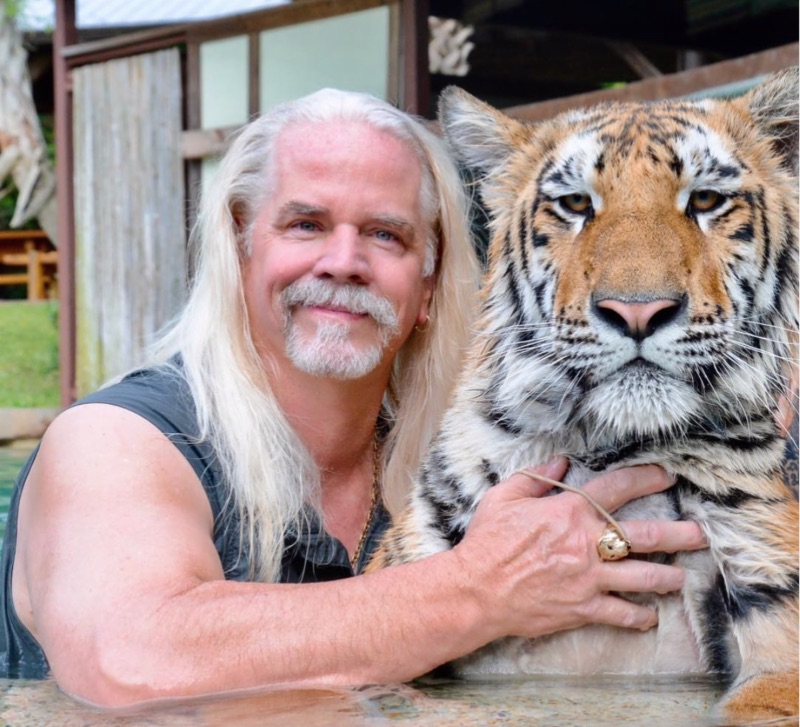

She has a similarly low opinion of Kevin “Doc” Antle, another eccentric animal abuser featured in the documentary. Antle has provided big cats and other animals for projects including the Ace Ventura films, a Jungle Book adaptation, a Britney Spears performance and an appearance on Oprah Winfrey’s talk show.

Earlier this year he was convicted of illegal wildlife trafficking in Virginia, where authorities said he tried to buy endangered lion clubs in violation of federal law. He’s racked up almost three dozen USDA violations for mistreatment of animals over the years, has been accused of gassing adult tigers to “make room” for more cubs, and faces a slew of additional charges related to money laundering and the alleged import of wild animals, including a chimpanzee and a cheetah.

Antle has also raised the ire of animal welfare advocates and conservationists for the controversial practice of breeding ligers — massive cats that are the result of breeding male lions with female tigers — and inbreeding tigers to produce a color morph commonly known as white tigers. While the latter are beautiful, majestic and rare, intentionally trying to breed them often results in cubs with malformations who either die in infancy or live short, brutal lives.

Guard does not regret the time she spent working with big cats on Regan’s ranch, just the naïve way she went about it. Like others who have spent years thinking about how to best protect and save big cat species, she’s come to the conclusion that the majestic felids are best helped — and appreciated — from a distance.

At the ranch, some of the felids were former show animals rescued from the entertainment business. Some, like Saigon, were abandoned young by people who had planned to use them in shows. Others were like Tsavo the lion, who “came from a shitty private owner.”

Regan was a former tiger trainer for circuses but had changed his views on using the animals for entertainment. He “was fastidious about taking care of the cats, very invested in their welfare and had only the best care for them,” she said. The ranch was sprawling, with enrichment items and toys everywhere, as well as a large lake with an island in the middle so the cats — particularly tigers, who are known for their love of water — could swim and play. At night they settled into their own individual habitats, each equipped with smaller pools, entertainment items and bedding.

In addition Wayne, Guard and their volunteers were reluctant to display the cats for anyone, even donors. They felt it would be a betrayal to the animals to be gawked at in a place that had become a haven for them.

Regan had learned the business from a man named Ron Whitfield, who remains active in the big cat community as the large carnivore curator at the San Francisco Zoo and trained animals for 30 years at the now-defunct Marine World in San Francisco.

“The business is so small that word gets around and Wayne, and Ron too, were known as good people to care for unwanted animals,” Guard said.

These days, Guard cares for small cats too as a caretaker and feeder of stray cat colonies in her California neighborhood. It’s a reminder of the good people can do in their own backyards, and of the need that exists in a country where some 800,000 unwanted felines are euthanized every year despite Herculean efforts to push spaying and neutering. (Those efforts have been very successful, and euthanizations of cats and dogs are only a fraction of the millions they were just 15 years ago, but the fact that so many unwanted animals are still killed illustrates the enormity of the problem.)

Mostly, she wants people to know that the idea of having a big cat for a companion, or even living in something resembling harmony with them, “is a fool’s paradise.” Luck is the only determining factor in whether a handler lives or, as Siegfried and Roy can attest, suffers life-altering injuries from accidentally triggering the ever-present predatory instinct of tigers, lions and other big cats like jaguars and leopards.

They are, after all, the planet’s apex predators, hyper-carnivores designed by nature with the most deadly weapons of any extant animal.

Guard says she hopes the practice of keeping big cats truly ends after the current generation of panthera “pets” — those grandfathered in under the Big Cat Public Safety Act — pass on. And she hopes that young people who are as “spellbound and mesmerized” by the spectacular felids as she was don’t follow her lead and endanger their lives, which is why she’s brutally honest about her own experiences and makes no pretense about benefiting from any factor other than luck.

“It’s been a long road for me to go from there to here,” she said. “I’m glad I can recognize my mistakes and hope I can prevent others from doing the same. I don’t know why people are drawn to do dangerous things but for me I didn’t think about the danger because I just wanted to be close to my cats.”

She understands the allure, but always comes back to the same conclusion: humans and big cats are not meant to live side by side.

“The cost is too great if something goes wrong,” she said. “And something always goes wrong given enough time.”

Did you like this story? Read some of PITB’s other long-form journalism and essays:

Government Biologist Who Shot Cats Called Their Corpses ‘Party Favors’ In Email Celebrating Their Deaths

Ode To Cosmo: The Best Dog I’ve Known

Demon of Champawat: The Man-Eating Tiger And The Hunter Who Put An End To Her Bloody Reign