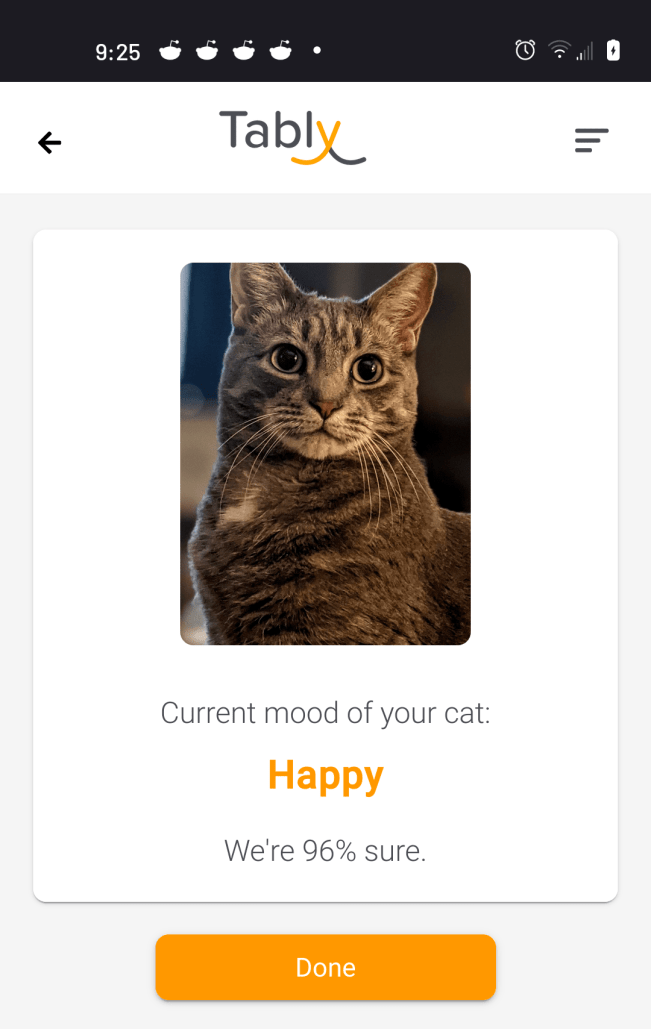

Check out our newest feature, catwire!

When you think of a crime scene, you probably picture uniformed officers manning the perimeter, crime scene tape cordoning off the room where the deed was done, detectives trying to reconstruct what happened, and techs collecting evidence.

Those techs might swab surfaces for traces of a suspect. Drinking cups and water bottles might be dusted for fingerprints, stray hair might be bagged and sent back to the laboratory for analysis. Discarded cigarette butts, door handles, buzzers — they can all yield evidence, to say nothing of cell phones, USB sticks and smart appliances.

But what about the pets? If a suspect was especially careful not to leave prints or touch anything at the crime scene, could the fur of a cat harbor DNA?

A team comprised of scientists from Australia’s College of Science and Engineering at Flinders and the Victoria Police Forensic Services Department wanted to know if cat fur could indeed hold critical evidence at crime scenes, so they conducted a study involving 20 pet cats from different homes, and what they found could provide an important tool for law enforcement. Their findings were published in the journal Forensic Science International.

If detectives are trying to piece together the identities of robbers who, say, broke into a home, brutalized the people there at gunpoint and stole their valuables, they can’t interview the victims’ pet cats about what they saw, but it turns out they can swab the kitties’ fur and have an excellent chance of retrieving useful DNA.

The research team swabbed the fur of pet cats in their test households, took DNA samples of the adults living in those homes — who were the stand-ins for victims — and asked the human participants to fill out surveys asking about their cats, what they do on a typical day, and whether or not they have interaction with people outside the home.

After the team conducted DNA analysis on the fur swabs “[d]etectable levels of DNA were found in 80% of the samples and interpretable profiles that could be linked to a person of interest were generated in 70% of the cats tested,” the study authors wrote.

While most of the samples matched the DNA of people who lived in the homes — as expected — samples from six cats revealed the presence of DNA from other people. The research team didn’t take DNA samples of minors, and two of the positive fur swab samples came from cats who lived in a home with a child and slept in that child’s bed most evenings. But four other samples turned up “mystery” DNA even though no one else had visited those homes for at least several days.

For DNA from pets to have any real evidentiary value, prosecutors have to prove a “chain of custody” of sorts, establishing that suspects could not have had contact with the animals in question unless they were inside a home where a crime has taken place. If the cat is allowed to roam outdoors every day, for example, it becomes much more difficult to prove a suspect’s DNA was transferred to a pet inside a home rather than on the street.

That’s why the research team is hopeful, but also cautions that their study is a first step toward understanding more about how human DNA is transferred to fur, whether it requires a person to be physically present (as opposed to their DNA being passed along secondhand in stray hair or skin cells), how long a cat’s fur can harbor human DNA, and other questions prosecutors will have to answer.

“This type of data can help us understand the meaning of the DNA results obtained, especially if there is a match to a person of interest,” said study co-author Mariya Goray, a DNA transfer expert. “Are these DNA finding a result of a criminal activity or could they have been transferred and deposited at the scene via a pet?”

The team recommends more research “on the transfer, persistence and prevalence of human DNA to and from cats and other pet animals and the influences animal behavioral habits, the DNA shedder status of the owners and many other relevant factors.”

If they do answer the aforementioned questions and prosecutors believe they can establish a suspect’s presence at a crime scene thanks to feline-provided evidence, it might not be too long before we see a cat-centric episode on future seasons of Law & Order or CSI, both of which are scheduled to be revived as police procedurals enjoy a resurgence on TV.