According to dozens of articles, a pair of new studies throws doubt on the commonly-held view that cats self-domesticated 10,000 years ago by helping themselves to rodents invading human grain stores.

The conventional wisdom for some time has been that house cats are the domesticated ancestors of felis sylvestris lybica, the African wildcat. Their genomes are nearly identical, it’s often difficult even for experts to tell the species apart, and they’re much more tolerant toward humans than the comparatively hostile felis sylvestris, the European wildcat.

But two new papers are raising eyebrows for their fantastic claims that feline domestication was actually human-driven and began about 5,000 years ago in Egypt.

Specifically, the papers claim cats were sacrificed en masse by the cult of Bastet, an Egyptian feline goddess, guiding the species toward domestication in a way that doesn’t quite make sense with what we know of evolution.

There are two main elements to the new claim:

- The earliest grave in which a cat was buried with a human was dated to about 10,000 years ago, and was found in Europe. But an analysis of the cat’s remains indicate it had DNA somewhere between a wild cat and a domestic feline. That, the authors claim, throws into doubt the idea that cats drifted into human settlements, drawn by the presence of rodents.

- If domestication was closer to 5,000 years ago, that would coincide with the rise of the cult of Bastet, the Egyptian cat goddess, around 2,800 BC.

Instead of the feel-good, fortuitous sequence of events the scientific community has accepted as the likely genesis of our furry friends, the authors of the new papers claim aggressive and fearful traits were essentially murdered out of the feline population by Bastet cultists who sacrificed cats in large numbers and mummified their corpses.

Neither paper has been peer-reviewed yet, and experts on ancient Egypt, genetics and archeology have already begun pushing back.

The new timeline, they say, doesn’t quite add up, with cat mummies found throughout different periods in Egyptian history, not just during the height of Bastet’s popularity in the Egyptian pantheon. Bastet’s popularity came approximately 700 years later than the authors claim the sacrifices began, and early imagery of the felid goddess depicts her with a lion head. It wasn’t until later centuries that Bastet was represented with the features of a domestic cat.

Separate from timeline concerns is the lack of historical evidence. Cats were revered in ancient Egypt, and while there are an abundance of cat mummies — as well as the mummified remains of many other animals — that does not mean the cats were ritually sacrificed.

Indeed, archaeological, hieroglyphic and anthropological evidence all show cats enjoyed elevated status in the Egypt of deep antiquity, long before the nation became a vassal state of the Greeks, then the Romans.

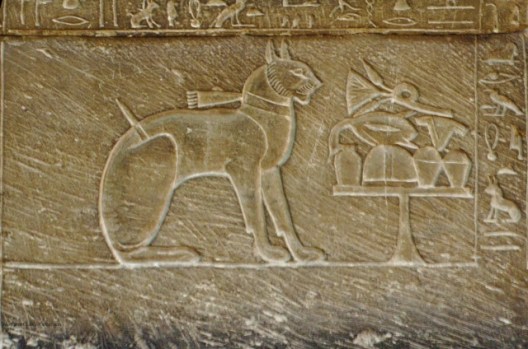

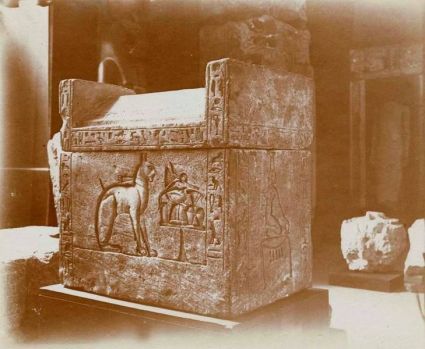

Cats were associated with magic, the divine and royalty, and cats who were the favored pets of Egyptian elites were given elaborate burials. Like Ta-miu, Prince Thutmose’s cat who is known for her grand sarcophagus decorated with images of felines and prayer glyphs meant to guide her to the afterlife.

Cats were sacred companions to the Egyptians

When cats are found buried with humans, the more common explanation is that those cats were the pets and companions of those humans. If the authors of the two new papers want to prove their claim that cats were ritually sacrificed by the tens of thousands — slaughter on a scale that would influence evolution — they’ve got a lot more work ahead of them. (And the burden of proof rests squarely with them, as the originators of the claim.)

Not only does their research attempt to change the origin stories of kitties to an ignominious tale of human barbarity, if we take their assertions at face value, we’re talking about a case of “domestication by slaughter.”

While it may be true that the earliest evidence of companion cats outside of North Africa revealed hybrid DNA, that doesn’t cast doubt on the commonly-accepted view of feline domestication, it strengthens it. Domestication is a process that takes hundreds of years if not more, and it occurs on a species level, so it makes perfect sense that cats found in burial sites from early civilization would be hybrids of domestic and wild. Those felines were of a generation undergoing domestication, but not quite there yet.

Killing off docile cats?

Which brings us to another significant problem with the claim: if the ancient worshipers of Bastet were selecting the most docile and easiest-to-handle wildcats for their sacrifice rituals, as claimed, then they would be influencing evolution in the other direction.

In other words, they’d be killing off the cats who have a genetic predisposition toward friendliness, meaning those cats would not reproduce and would not pass their traits down. It would have the opposite effect of what the papers claim.

So despite the credulous stories circulating in the press and on social media, take the assertion with a grain of salt. Something tells me it won’t survive peer review, and this will be a footnote about a wrong turn in the search for more information on the domestication of our furry buddies.