A New Zealand man says he filmed a “panther” after taking blurry footage of a house cat.

Kyle Mulinder does his best Steve Irwin impression with a breathless “Look at that thing! Amazing!” while zooming in on what looks an awful lot like a domestic cat.

Mulinder continues to provide commentary and generously estimates the cat at “four foot high” as it dashes off a dirt road into a wooded area in New Zealand’s Hanmer Springs Heritage Forest.

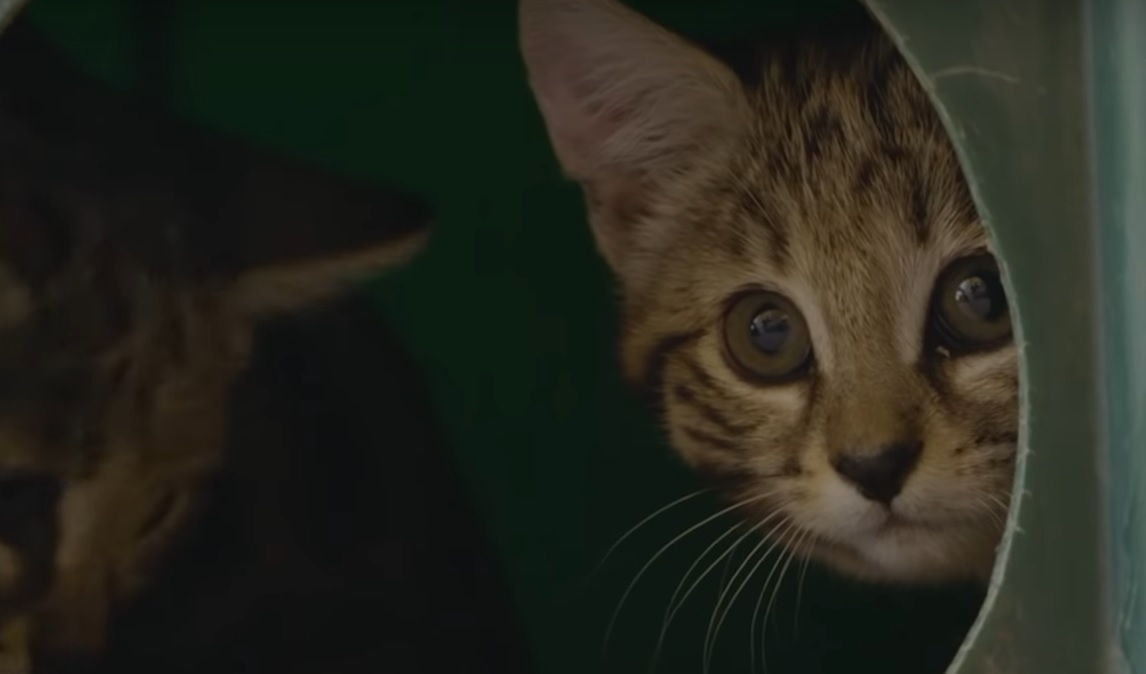

Here’s a screenshot of the cat. I wasn’t able to embed the video, so you’ll have to visit the New Zealand Herald to watch it.

A handful of New Zealanders have said they’ve seen a large cat since at least this summer, long enough for the local press to dub the cat the Canterbury Panther. Various reports identify the cat as grey, tawny or black.

Mulinder, who calls himself Bare Kiwi online, demonstrated a flair for the dramatic while telling his tale to the Herald.

“It was about 50 metres away, strolling in the other direction but it sat down, turned and looked into my soul,” Mulinder said. “It was a very emotional experience. I was fearing for my life.”

(Insert terrifying Buddy joke here.)

Yolanda van Heezik, a zoologist at New Zealand’s Otago University, said the chances of a big cat on the loose are “extremely unlikely.”

Aside from the lack of convincing footage of the Canterbury Panther, there aren’t any obvious signs of a mountain lion, jaguar or leopard, van Heezik said. Those signs could include scratches from large claws high up in trees, widespread scent-marking and the trail of prey that would be left by a large carnivore.

“No one’s ever caught one, no one’s ever got really good evidence that they are something different from just a large feral cat,” she said earlier this month. “And there’s also a complete lack of evidence that is indirect like if you had a really big cat like that you would expect there to be more stock kills, for example, but we don’t really have that evidence either.”

Aside from the cat’s small size, there are other obvious reasons why it’s unlikely to be a panther. The word panther can refer to a cougar, also known as a mountain lion or puma. It can also refer to a jaguar or a leopard.

None of those cats are found on New Zealand: Pumas and jaguars are native to the Americas, while leopards exist in Africa and parts of Asia.

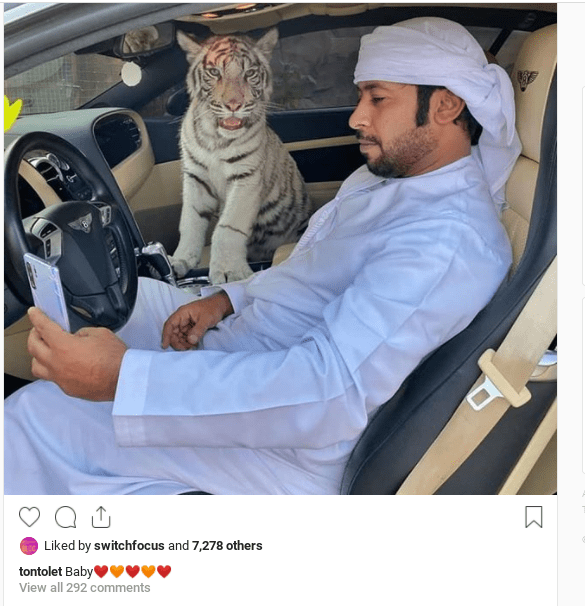

Of course it’s possible someone purchased a big cat from the illegal wildlife market and the animal escaped or was let go, but those cases are rare and big cats tend to be the “toys” of the ultra-wealthy. Local authorities have ruled out the possibility of a large cat escaping from any nearby zoo or wildlife facility, according to the Herald.