I’ve been watching Apple TV’s exceptional show, For All Mankind, which dramatizes the space race of the 1960s and beyond in a sort of alternate history where the Soviets, not Americans, first lay boots on the lunar regolith.

That loss lights a fire underneath the behinds of the people at NASA and convinces American politicians that the space race is the ultimate measure of our civilization. In real life, American ingenuity and the creativity fostered by a free society allowed the US to leap ahead and “win” the space race. Space missions were already becoming routine by the time the drama of Apollo 13 briefly rekindled public interest.

Then the Soviet space program faded, the competition turned one-sided, and without an arch-enemy to show up, American politicians pulled back NASA’s funding to a fraction of what it once was, where it remains today. That’s why the rise of the private space industry — Elon Musks’s Space X, Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, etc — will almost certainly be our ticket to Mars.

But in For All Mankind, NASA remains the budgetary behemoth and source of prestige it was in the 60s and 70s, leading to the development of a permanent moon base, lunar mining operations and a planned mission to the red planet.

There’s a quiet moment in the second season when a Soviet cosmonaut, visiting the US as part of a peacekeeping mission, shares a drink in a dive bar with an American astronaut.

“Do you like dog?” the cosmonaut asks.

“Dogs?” the astronaut replies. “Of course. Who doesn’t like dogs?”

The Soviet shakes his head.

“No, dog,” he tells her. “Laika.”

Laika was the first dog in space, or more accurately, the first dog the Soviets acknowledged sending into space. (The Soviets didn’t acknowledge their failures, and we can only guess at the number of lost cosmonauts and animals officially denied by the Russians, drifting in space for eternity or disintegrated in atmospheric re-entry.)

The moment turns somber as the cosmonaut recalls the Moscow street dog who was selected because she was docile, fearless and could handle the incredible noise and g-forces of a rocket launch.

“I held her in my arms,” the cosmonaut tells his American counterpart, taking a sip of his Jack Daniel’s. “For only one or two minutes on the launchpad.”

Then he leans in and tells her the truth: Laika didn’t triumphantly orbit the Earth for seven days in 1957 as the Soviet Union told the world. She didn’t endure the mission.

She perished, alone and afraid, just hours after launch when her capsule overheated.

The Soviets never designed the Sputnik 2, Laika’s ship, to return to Earth safely. Her death was predetermined.

We laud astronauts and cosmonauts, the brave men and women who willingly strap themselves into tiny capsules attached to cylinders of rocket fuel the size of skyscrapers and depart this Earth via brute force, knowing something could go wrong and their lives could end before they realize what’s happening. We should admire them. Their accomplishments are all the more impressive when you consider the fact that the combined processing power of every computer at NASA’s disposal in the 1960s was but a fraction of what we each hold in our hands these days when we use our smartphones.

Those first astronauts and cosmonauts were extraordinarily brave — but only up to a point.

Unwilling to risk human lives in the early days of space exploration, space programs used dogs, cats and later monkeys and apes, strapping them into confined spaces, wiring their brains with electrodes for telemetry data, poring over the information they gleaned about their heart rates, blood pressure and breathing as they left our home planet.

The sad eyes of a stray dog, separated from everyone she loved, were the first to behold Earth from space. A few years later the eyes of a French street cat took in the same view before humans did.

Felicette, the tuxedo cat who was launched into space by the French on Oct. 18, 1963, didn’t even have a name until the French recovered her capsule and took her back for examination.

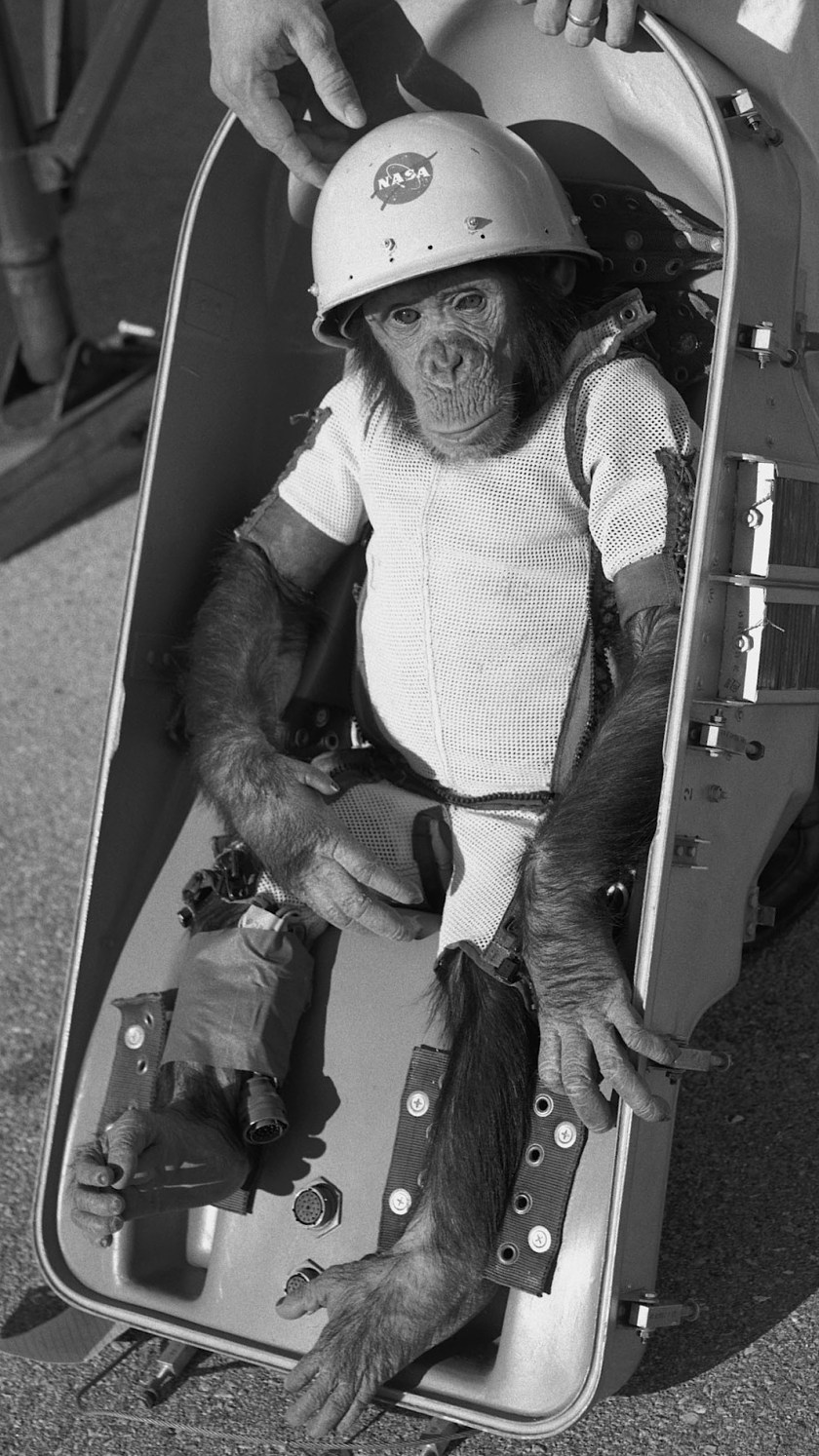

The scientists and engineers in charge of the launch didn’t want to humanize her if she didn’t make it, which was a common practice in space programs. (Ham, the chimpanzee sent into space by NASA in January of 1961, was known as No. 65 until his successful recovery. NASA was worried that a name would make him more sympathetic and lead to bad press if the chimpanzee died during the mission.)

Despite Felicette’s endurance and successful return, French scientists repaid her bravery by euthanizing her a month later so they could study her brain and learn more about the effects of spaceflight on mammalian biology.

Felicette, like Laika and Ham, was never given a choice. Those animals, with their child-like mental capacity, endured their missions out of a desire to please their human caretakers as much as any natural stoicism they may have possessed.

Would we do the same thing today? Will we repeat those experiments as we set our eyes on Mars?

Consider that the moon is a three day trip, and it’s close enough to Earth’s magnetic field to protect living beings from radiation. Mars is at least a seven month trip if the orbital conditions are right, and there will be no protection from radiation aside from what can be built into the craft. Take that trip without adequate protection and you’re guaranteed to get cancer.

It’s easy to say we wouldn’t make animals our test subjects for a Mars journey, and NASA now has decades of data on the effects of space and zero gravity thanks to the International Space Station.

And yet Neuralink, another company owned by Elon Musk, currently uses monkeys to test its brain interface technology, which allows the primates to operate computers with their thoughts. Those monkeys are forced to endure radical surgery to implant microchips in their brains. The teams working on the technology say suffering by those animals will be worth it as people with paralysis are able to do things with their thoughts and regain a measure of independence, increasing their quality of life.

Likewise, it will probably be an animal, or animals, who will be the test subjects on board craft that first venture beyond the Earth’s protective magnetosphere. Scientists and engineers will do their best to create a vessel that shields its occupants from harmful radiation, but they won’t know how successful they’ve been until the test subjects are returned to Earth and their dosimeters have been examined.

Will an astronaut volunteer for that kind of mission, knowing the “reward” could be a drastically shortened life?

To hear Musk and futurists tell it, pushing toward Mars is not just a matter of exploration or aspiration, but is necessary for the survival of our species. Earth becoming uninhabitable, they say, is an eventuality, not an if.

Others point out it’s much easier and wiser to pour our resources into preserving the paradise we do have, and the creatures who live in it, rather than banking on a miserable future existence on Mars where society will have to live underground and gravity, at 0.375 that of Earth, will change the human form in just a few generations.

To put it bluntly, while Musk and futurists look at life on Mars through the rose-colored glasses of science fiction fans, in reality living there is going to thoroughly suck.

If people do live on Mars they’ll never venture outside without a suit, never feel the sun on their skin, never swim in an ocean. They’ll never have another backyard barbecue, watch fireworks light up the sky on the fourth of July, or fall asleep to the gentle rain and crickets of warm summer nights. They’ll never hear birdsong or have the opportunity to see iconic animals like elephants and lions. Every gulp of air will be recycled, every glass of water will have passed through the kidneys of others. There will never be snow. Circadian rhythms will be untethered from the cycle that governed human biology for the 200,000 years our species has existed.

And while there could be a future — if you want to call it that — for people on Mars, there won’t be a future there for the rest of the living creatures on Earth.

As a lifelong fan of science fiction who devours SF novels, counts films like Alien and Bladerunner among my favorites, and is fascinated by shows like For All Mankind, The Peripheral and Star Trek, I understand the appeal of space and the indomitable human spirit that drives us to new frontiers. I just hope we can balance that with respect for the Earth and the animals we share it with. Let’s hope there is never another Laika, Felicette or Ham.

Correction: For All Mankind is the name of the Apple TV series about an alternate history space race. The first reference to the show’s name was incorrect in an earlier version of this story.