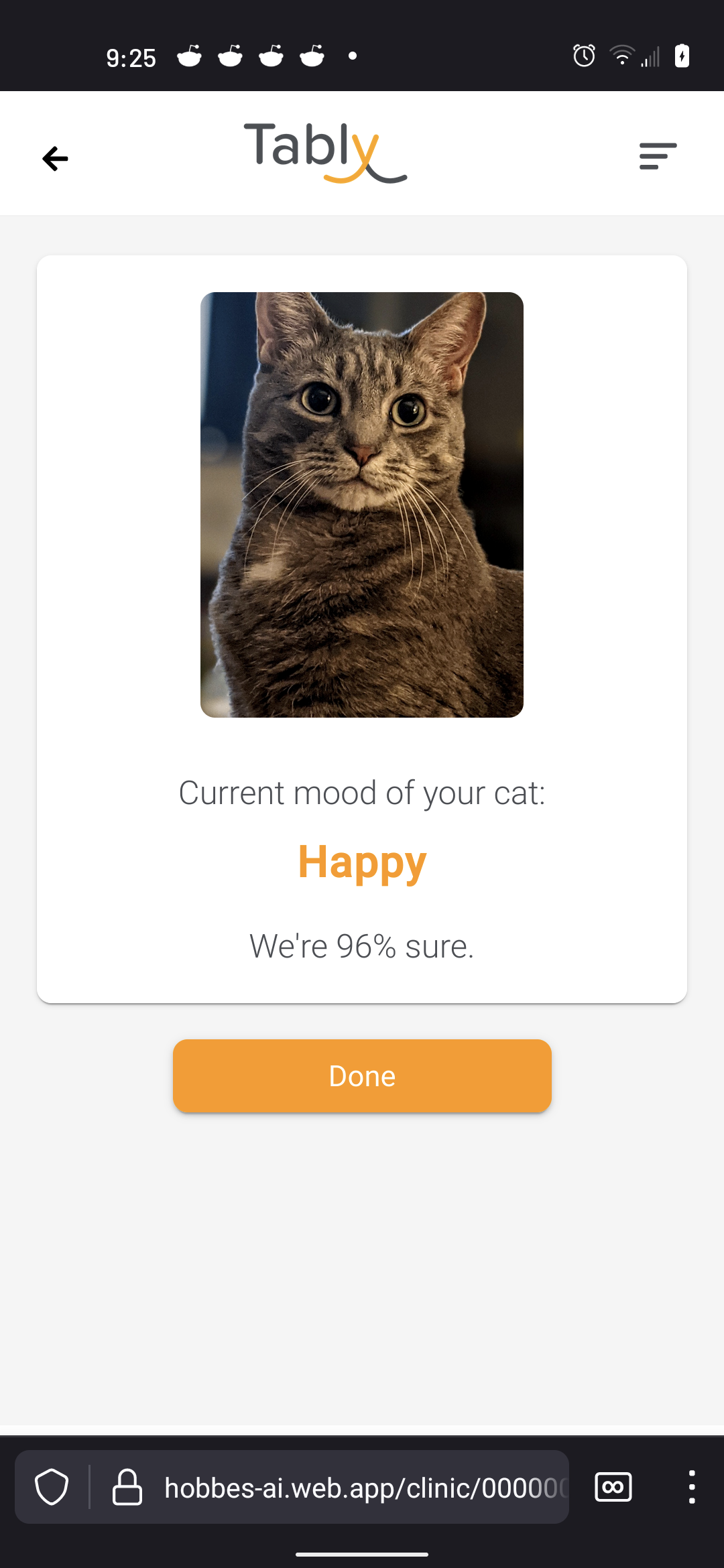

In the photograph, Buddy is sitting on the coffee table in the classic feline upright pose, tail resting to one side with a looping tip, looking directly at me.

The corners of his mouth curve up in what looks like a smile, his eyes are wide and attentive, and his whiskers are relaxed.

He looks to me like a happy cat.

Tably agrees: “Current mood of your cat: Happy. We’re 96% sure.”

Tably is a new app, currently in beta. Like MeowTalk, Tably uses machine learning and an algorithmic AI to determine a cat’s mood.

Unlike MeowTalk, which deals exclusively with feline vocalizations, Tably relies on technology similar to facial recognition software to map your cat’s face. It doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel when it comes to interpreting what facial expressions mean — it compares the cats it analyzes to the Feline Grimace Scale, a veterinary tool developed following years of research and first published as part of a peer-reviewed paper in 2019.

The Feline Grimace Scale analyzes a cat’s eyes, ears, whiskers, muzzle and overall facial expression to determine if the cat is happy, neutral, bothered by something minor, or in genuine pain.

It’s designed as an objective tool to evaluate cats, who are notoriously adept at hiding pain for evolutionary reasons. (A sick or injured cat is a much easier target for predators.)

But the Feline Grimace Scale is for veterinarians, not caretakers. It’s difficult to make any sense of it without training and experience.

That’s where Tably comes in: It makes the Feline Grimace Scale accessible to caretakers, giving us another tool to gauge our cats’ happiness and physical condition. With Tably we don’t have to go through years of veterinary training to glean information from our cats’ expressions, because the software is doing it for us.

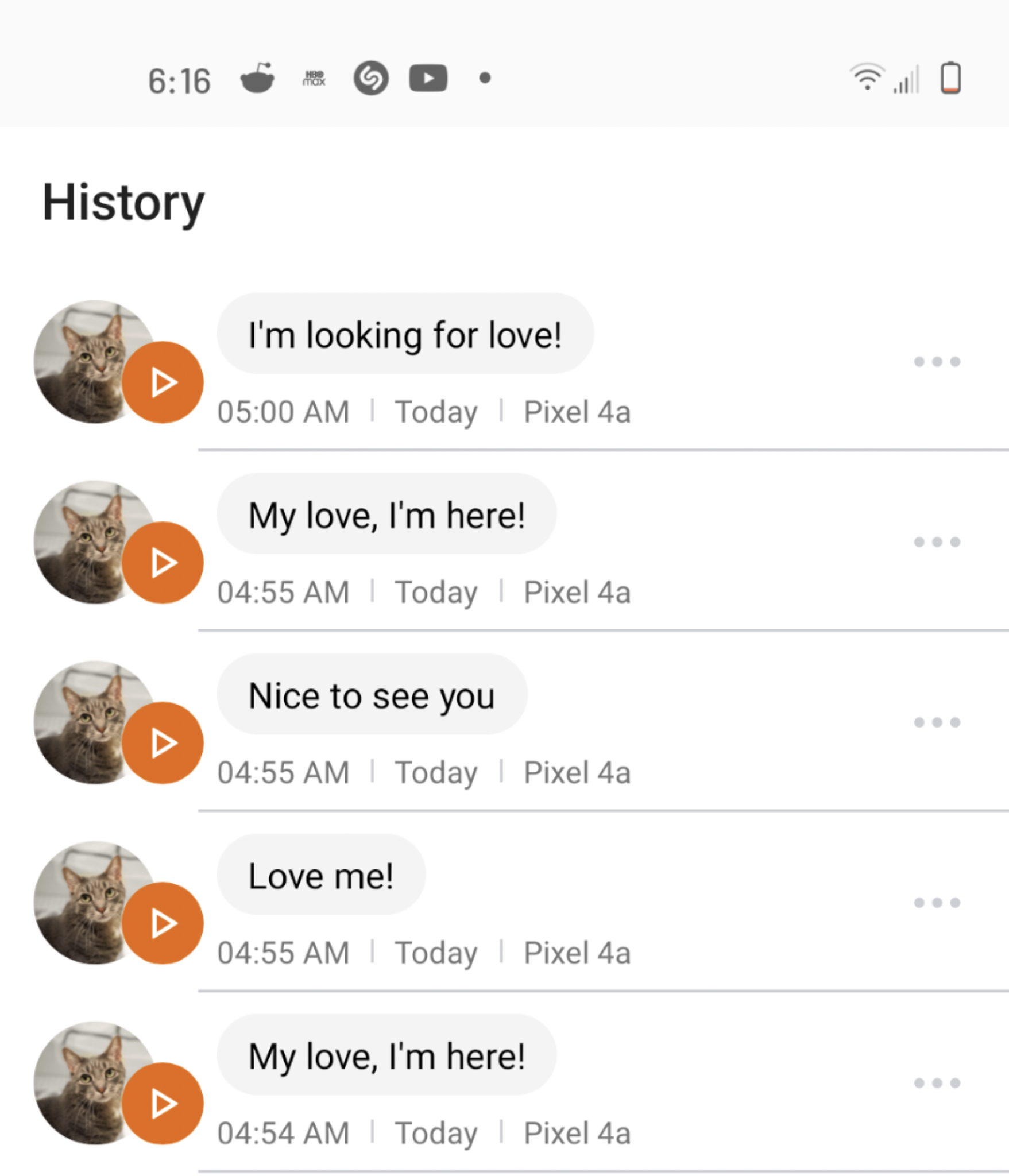

Meanwhile, I used MeowTalk early in the morning a few days ago when Buddy kept meowing insistently at me. When Bud wants something he tends to sound whiny, almost unhappy. Most of the time I can tell what he wants, but sometimes he seems frustrated that his slow human isn’t understanding him.

I had put down a fresh bowl of wet food and fresh water minutes earlier. His litter box was clean. He had time to relax on the balcony the previous night in addition to play time with his laser toy.

So what did Buddy want? Just some attention and affection, apparently:

I’m still not sure why Buddy apparently speaks in dialogue lifted from a cheesy romance novel, but I suppose the important thing is getting an accurate sense of his mood. 🙂

So with these tools now at our disposal, how much can artificial intelligence really tell us about our cats?

As always, there should be a disclaimer here: AI is a misnomer when it comes to machine learning algorithms, which are not actually intelligent.

It’s more accurate to think of these tools as software that learns to analyze a very specific kind of data and output it in a way that’s useful and makes sense to the end users. (In this case the end users are us cat servants.)

Like all machine learning algorithms, they must be “trained.” If you want your algorithm to read feline faces, you’ve got to feed it images of cats by the tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands or even by the millions. The more cat faces the software sees, the better it gets at recognizing when something looks off.

At this point, it’s difficult to say how much insight these tools provide. Personally I feel they’ve helped me understand my cat better, but I also realize it’s early days and this kind of software improves when more people use it, providing data and feedback. (Think of it like Waze, which works well because 140 million drivers have it enabled when they’re behind the wheel and feeding real-time data to the server.)

I was surprised when, in response to my earlier posts about MeowTalk and similar efforts, most of PITB’s readers didn’t seem to share the same enthusiasm.

And that, I think, is the key here: Managing expectations. When I downloaded Waze for the first time it had just launched and was pretty much useless. Months later, with a healthy user base, it became the best thing to happen to vehicle navigation since the first GPS units replaced those bulky maps we all relied on. Waze doesn’t just give you information — it analyzes real-time traffic data and finds alternate routes, taking you around construction zones, car accident scenes, clogged highways and congested shopping districts. Waze will even route you around unplowed or poorly plowed streets in a snowstorm.

If Tably and MeowTalk seem underwhelming to you, give them time. If enough of us embrace the technology, it will mature and we’ll have powerful new tools that not only help us find problems before they become serious, but also help us better understand our feline overlords — and strengthen the bonds we share with them.