The Swiss seem to take cat theft pretty seriously, to the point where they’re perfectly willing to drag people to court for feeding other people’s cats.

That’s what happened to a 68-year-old woman in Zurich who is accused of being so nice to Leo, a neighbor’s cat, that the little guy decided her house was now his house.

According to local media reports, a Zurich prosecutor wants to fine her 3,600CHF (Swiss francs), which is $4,370 in ‘Merican greenbacks! That’s a lot of money for giving a cat some Temps and cans of tuna.

To be fair, Leo’s original family isn’t happy, especially because they specifically asked the woman to stop feeding their cat. She can’t claim she accidentally adopted him, since she let him into her apartment and even installed a cat flap for him, according to Swiss media reports.

“Cases like this are increasingly ending up in court because the rightful owners report the “feeders”. Under Swiss law, cats are “other people’s property” and systematic feeding and giving a home to another person’s cat is considered unlawful appropriation.

But if a neighbour’s cats are only fed occasionally, this is not a punishable offence in Switzerland.”

There’s really not enough information to form an opinion about this particular case. Was Leo mistreated or not getting enough to eat? Did his new human have designs on him from the beginning? Did she just think she was doing the right thing?

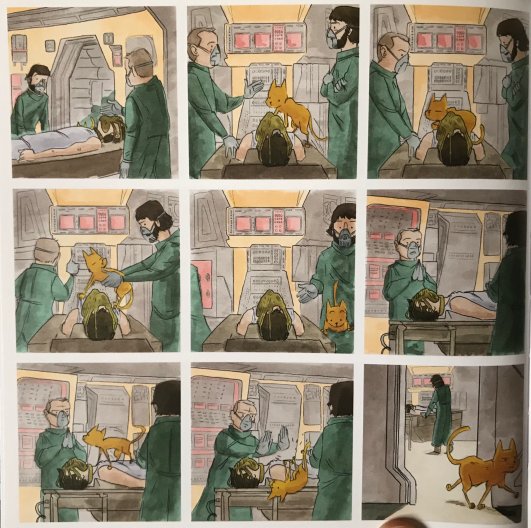

As for me, this is another good reason to keep Bud inside. If I let him roam the halls of the building unsupervised, he’d probably start a bidding war between me and neighbors in two or three other apartments, making it clear that whoever supplies him with the most delicious and most frequent snacks will enjoy the great honor of serving him.

Kids identifying as cats: the fake controversy that won’t die

Just a quick recap, for anyone who hasn’t been keeping up on this uniquely American culture war spectacle: Politicians of a certain stripe really like rumors about kids identifying as cats, so much so that they’ve confidently asserted it’s happening all over America, telling anecdotes about it while on the campaign trail during the 2020, 2022, and 2024 political cycles.

That encompasses two presidential elections and a midterm year, but it’s not relegated to federal cycles. State-level pols love to talk about it too.

It’s a culture war dog whistle, and politicians from both parties love stuff like this because it gets everyone all riled up, which means no one’s talking about all the grift, insider trading and other fun activities our “leaders” involve themselves in.

The thing is, to date not a single one of the claims has been backed up by proof. I know this because I’ve investigated every one of them, and invariably they turn out to be rumors. I’ve gotten emails and comments telling me I’m a fool for debunking the claims, and I’ve literally begged people to give me a real example of cat-identifying kids dropping deuces in litter boxes, but again, all the claims collapse under minimal scrutiny.

Every time a politician has told a story about allegedly cat-identifying kids and litter boxes in schools, it follows the same pattern: they insist it’s true, double down on the claim, try to change the goalposts, and finally, they grudgingly admit they can’t point to a single example.

In a week or two, we go from righteous condemnation and fury to “Well, my wife’s best friend teaches sixth grade, and she said she heard from a teacher in another district that kids were meowing in class.”

Texas state Rep. Stan Gerdes is in the righteous condemnation stage after introducing the Forbidding Unlawful Representation of Roleplaying In Education Act, aka the FURRIES Act.

Gerdes wants to ban meowing, hissing, barking, litter boxes, leashes and animal costumes from school grounds and events, but in his wisdom he’s excluded school mascots and Halloween costumes.

He is, however, fast approaching the “my cousin’s best friend’s co-worker said” stage, after he couldn’t point to a single cat- or furry-related incident when pressed during a committee meeting on May 1. He eventually named a school district, saying he’d gotten a “extremely concerning” and verified account of an incident there, only for the district to issue a statement saying it didn’t happen.

Gerdes did call to ask if there were litter boxes in the school, the district said, and when he was told there was not, he insisted a manual check of all school bathrooms, which also came up empty. Let’s see how long he sticks to his story before he finally admits he has no proof.