I would love it if my cat could talk to me.

Sure, he never shuts up, but if he could speak English I’d know why he meows at the same spot at the same time every morning, or what he wants on the occasions when he’s still meowing insistently at me despite the fact that his bowls are full, his box is clean, he’s had his play time, and every possible need and want of his — that I can fathom — has been met.

Most of all, I’d really like to know he understands I’ll be back soon when I go away for a few days, and my (mostly ignored) pleas for him not to attack his long-suffering, way-too-kind sitter.

Alas, Bud cannot speak. No non-human animal has ever demonstrated even basic proficiency in human language. People will point to examples like Koko the Gorilla and Nim Chimpsky, but there’s a reason why funding dried up for that kind of experiment.

It doesn’t work. It never did.

The scientists who end up taking on dual roles as researchers and parents to the animals invariably serve as interpreters, get too close to their subjects and swear that a gorilla pounding shiny buttons for “food tree food submarine” means the ape wants to have a picnic next to the ocean, or “car fly house car star” means she wants to ride a Tesla Roadster to Mars and start a colony with Elon Musk.

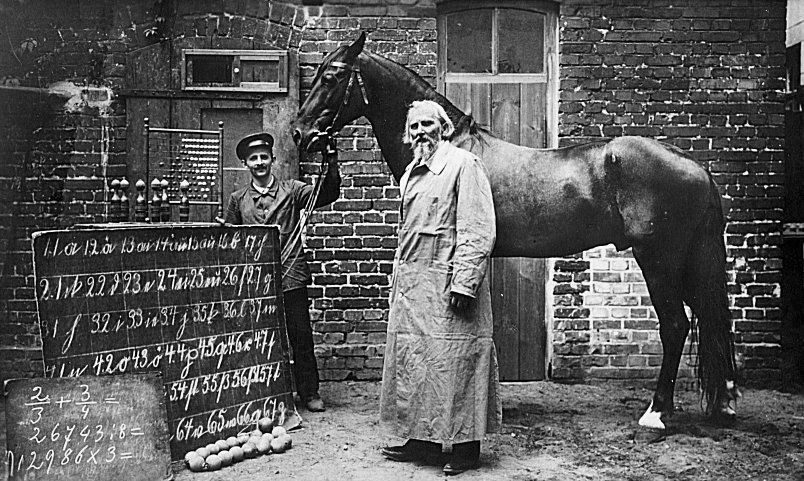

Koko, Nim, Chantek and the other apes who were the subjects of decades-long attempts to humanize them — and teach them language in the process — were ultimately not much different than Clever Hans the horse, who was reading subconscious nonverbal cues from his owner and convinced tens of thousands of people that he could do math and understand spoken language.

Hans had scores of experts fooled until the German psychologist Oskar Pfungst figured out how the horse was coming up with the correct answers.

Regardless of which famous example we’re talking about, no animal has ever mastered syntax, and the best that could be said of their proficiency with language, or lack of it, is that they learned they’d get attention and food when they pounded on a talking board or approximated a word in sign language.

Even if non-human primates were able to learn a handful of words by frequently reinforced association with an object, there has never been any evidence that they are actually using the words as language rather than simply understanding “Pushing the button that makes this sound means I get a treat!” (And yes, there is a profound difference. The former reveals the presence of cognitive processes while the latter is a conditioned response.)

Despite decades of intense effort, no animal has ever demonstrated the ability to use human language. At best an animal bangs on a few buttons and people are left to speculate on the intent. Maybe Fluffy likes the way a certain word sounds. Maybe it’s just fun to hammer on buttons the way it’s fun to pop bubble wrap. Most likely, these cats and dogs know that using a talking board is a guaranteed way to get attention, a treat and a head scratch from their caretakers.

Influencers and their talking boards

TikTok, which spawns inane trends with the reliability of an atomic clock, has provided a platform for people who insist their cats and dogs can talk. Using “talking boards” — elaborate set-ups in which words are assigned to their own buttons — they “teach” their cats how to express themselves in English and provide proof in the form of heavily edited, out-of-context clips that require the same sort of creative interpretation pioneered by Penny Patterson, Koko’s caretaker.

I just watched a video in which a woman claims her cat, named after Justin Bieber, was describing an encounter with a coyote by stomping on buttons for “stranger,” “Justin,” “Mike,” and “stranger.”

The woman says she thought Justin was asleep at the time, but now she believes the orange tabby saw the coyote outside and was still stressing about it well into the next day.

While she’s repeating Justin’s “words” back to him, two of her other cats come by and step all over the talking board. I guess whatever they had to say wasn’t important.

Justin’s talking board has 42 buttons, which stresses credulity well beyond the breaking point. More than half of the buttons are used for abstract concepts.

But forget all that for a moment and ask yourself how our own efforts to decode the meow have been going.

Despite our status as intelligent, sapient animals, despite the powerful AI algorithms at our disposal, despite the benefit of being able to digitally record and analyze every utterance, we haven’t come close to a reliable method for interpreting feline vocalizations.

Likewise with dolphins, whale song, corvid calls and the sounds made by other animals at the top of the cognition pyramid.

Mostly, we’re learning we’ve underestimated the complexity of our non-human companions’ inner lives, especially when it comes to the kind of multi-modal communication humans also engage in, but only subconsciously. We say what we want with our mouths, while our eyes, facial expressions and body language say what we’re actually thinking.

Likewise, the meow is an unnatural way for cats to communicate, and it contains only a fraction of the information cats are putting out there. It’s just that we can’t reliably read feline facial expressions, let alone tail, whisker and posture. (Studies have shown most of us, even when we live with cats, don’t get measurably better at this. In fact, we’re often no better than people with limited feline experience, but we think we’re better.)

Putting the burden on our furry friends

If we can’t crack a simple and limited system of vocalizations, aren’t we putting unrealistic expectations on cats? The average person has a vocabulary of tens of thousands of words, yet somehow we expect cats can latch on to an arbitrary number of them, approximate mastery of syntax that has eluded even our closest cousins, and bridge a cognition gap we haven’t been able to bridge ourselves.

It’s all too much.

There’s a simple truth at the heart of this: Cats did not evolve to speak or parse human language, and that’s perfectly fine.

The little ones already meet us more than halfway because they understand we are hopelessly incompetent at reading tail, whisker or body language, and they understand we communicate with vocalizations.

By forgoing their natural methods of communication in favor of ours, cats are already taking on most of the burden in interspecies communication. Asking them to do more than that, to learn many dozens of words and the rudimentary rules of language, seems like laziness, wishful thinking or insanity on our part. Pretending that certain cats are successful is an exercise in the same kind of cynical opportunism that fuels every other desperate attempt by people trying to turn their pets into influencers. People do it because the reward is money and attention.

Worse, it contributes to the spread of misinformation. TikTok’s talking board videos routinely net millions of views, converting a credulous audience into an army of true believers who are convinced that, with just a little effort, their feline pal can shoot the shit with them.

If people want to construct elaborate talking boards in their homes and pretend their cats are expressing themselves in English, who am I to object? It’s not the smartest use of time, but have at it. What I won’t do is participate in the delusion that felines are a few buttons away from being able conversation partners, nor will I pretend these efforts have any relationship to science.

So to the journalists who keep writing credulous stories about these supposedly talking animals: please familiarize yourself with the example of Clever Hans, and please, I beg you to stop promoting these videos as if they’re anything more than wishful thinking. You are doing your readers a disservice for the sake of a few clicks.

Note: Jackson Galaxy isn’t a fan either, saying he’s “got some serious problems” with the talking board trend. Calling it “problematic,” he points out that cats are not only partially domesticated and the only animal species in history to take that step without human prompting, but humans have never selectively bred cats for specific behaviors or to bring out intelligence traits as we have with canines. (Think of sheep dogs or retrievers, who are the products of thousands of years of breeding for well-defined tasks.) There simply hasn’t been a need to breed cats for behavioral traits since the thing humans traditionally valued most about them — their ability to reliably eradicate rodents and protect human foodstuffs — is innate. No one had to teach cats how to hunt or breed them for the task. It’s only in the last two hundred years or so that certain human societies began breeding cats, and they did so for aesthetic attributes like coat patterns. Galaxy also notes that animals do not express emotions the same way humans do. Like monkeys, who “smile” when they’re terrified, felines express joy, anger and fear with their tails, whiskers, ears and body language. It’s not in their nature to tell us they’re happy or scared by padding up to a contraption and hammering on a button.

Top image of “Justin Bieber” the cat credit Sarah Baker.