Look at what Youtube’s algorithm has served up for me: an “adorable” video of a baby monkey who loves to carry his equally small backpack!

Look at him. He loves it!

“That’s the cutest thing I’ve ever seen,” gushed one Youtuber.

“WHY IS THIS SO CUTE HELP ME,” another asks.

Others dub the video “so adorable,” “so cute” and call baby monkey Pika “the most adorable little baby I’ve ever seen.”

The video has five million views in four weeks. A handful of viewers might instinctively know something’s wrong while the vast majority of those people never give a second thought to what they’ve just watched.

Let me tell you what you’re looking at.

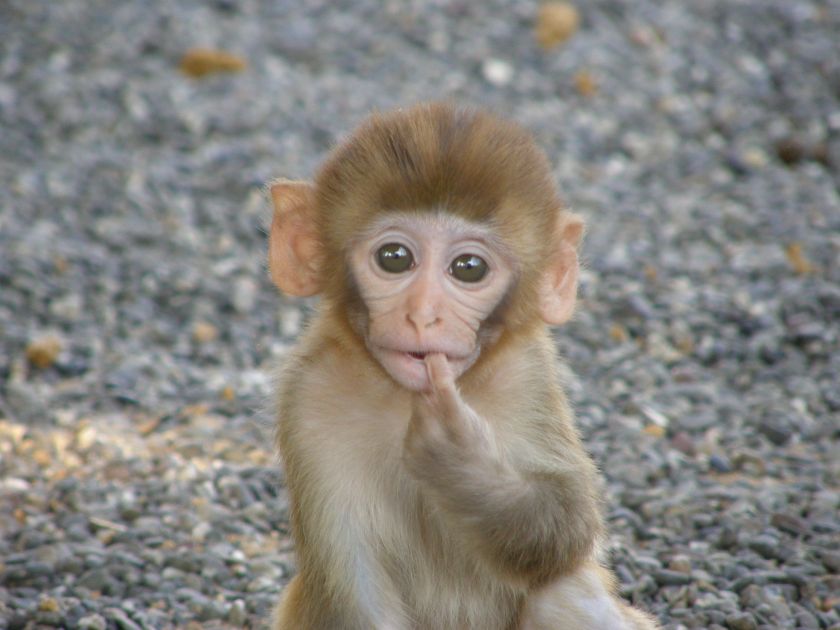

“Pika” is an infant rhesus macaque, about four weeks old by the look of him.

He is the “pet” of a woman in China, and to become her pet he was ripped out of his screaming mother’s arms as she fought tooth and nail to keep her grip on her baby. It’s at least a two-person job and the people who steal baby monkeys, either directly from the wild or from enclosures they own on breeding farms, up-armor themselves before going into the cage to protect from vicious bites and scratches.

Such is the fury of a mother whose baby is being taken from her.

(Above: An “adorable” video of an infant rhesus macaque who has been stolen from his mother and sold as a pet and has spent the first few weeks of his life being tortured to force him to walk on two feet. Right: A still from a video from a man who hunts monkeys titled “Baby Monkey Headshot”)

Pika was taken within a few hours to a few days after birth. No one wants adult monkeys so it’s imperative that the babies are swiftly “pulled” from their mothers, photographed and matched with buyers online. In the US an infant macaque will set you back about $5,000, but in China it’s considerably cheaper because the monkeys are native to Asia and certain parts of China, as well as neighboring countries and the territory of Hong Kong.

Being torn from his mother is just the first of many traumas Pika will endure in his guaranteed-to-be-miserable life.

Baby monkeys are a big thing in China, especially among the Mandarin-speaking nouveau riche of the mainland who have considerable disposable income and look for ways to signal their economic status to their peers. Expensive clothes, designer handbags, rare trinkets, you name it. If you’re a young upper class man perhaps you buy a sportscar. If you’re a young woman, you get a baby monkey, create a social media page and show everyone what a fantastic mother you’re going to be by clothing, feeding, training and disciplining the baby.

“Don’t monkeys walk on four legs?” you might be thinking. “They’re not bipedal, are they?”

No, they are not.

To walk upright, Pika has already endured the second major trauma of his young life: The human “mothers” take the little babies, tie their hands behind their backs, then tie a small rope or string around their necks. The other end is tied to an immovable object and the baby is given just enough slack that he can continue breathing if he remains upright.

This technique, borrowed from the topeng monyet (literally “dancing monkey”) trainers in Jakarta, forces the young monkey’s leg muscles to develop and forces his spine to become accustomed to rigidity.

For the first session, baby Pika would have been left like that for two, maybe three hours, likely screaming for his mother the entire time if his “owner” doesn’t put a stop to it with violence.

The intervals would increase steadily until he’s left like that overnight. Each time the rope is given less slack so Pika is forced to stand rigid.

Because they must have the strength and fine motor control to hold onto their mothers’ fur in the wild, macaque infants are ambulatory almost instantly, unlike the helpless infants of their primate cousins like orangutans and, well, humans.

The rope technique allows infants like Pika to quickly become accustomed to walking upright, but they will immediately revert to walking on all fours because that’s how they naturally move and that’s what their muscular-skeletal system is designed for.

That’s why Pika has a “cute backpack.” The backpack is filled with a counterweight so Pika must walk upright or fall over, giving his “owner” what she wants: A “cute” video to share on social media.

Of course Pika could simply refuse to walk, but then he’ll go hungry. Note the reason why he’s laboring, at just a few weeks old, with a counterweight on his back, with an unnatural gait to reach the other side of the room: the demon who purchased him is holding his bottle. No walk, no bottle. Walks, plural, because undoubtedly there were several takes.

(Pika may or may not have a tail. The “owners” often amputate them — without anesthetic — because they’re impediments for preemie diapers, and cutting tail holes in the diapers increases the chances of “accidents” spreading.)

Macaques are hyper-social creatures and they’re so similar to humans socially that psychologist Harry Harlow conducted his infamous maternal deprivation studies on infant rhesus monkeys like Pika.

In the wild babies like Pika will spend the first year of life clinging to mom and rarely straying more than a few feet from her. The mother-baby bond is so strong that daughters stay with their mothers for life, and sons stay until they’re five or six years old, at which time they’re booted from their home troops to avoid inbreeding.

The mothers do everything for their babies. They nurse them, groom them, protect them, soothe them when they scrape a knee and scoop them up when an older monkey is bullying them. Macaque babies nurse until up to two years old and they can frequently be seen hugging their mothers.

Through cruel experimentation Harlow found that the tactile feeling of being held in a mother’s arms is absolutely crucial to normal psychological development in primates, humans included. Harlow took infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers within hours and placed them in total isolation. Some babies were given inanimate “surrogate mothers” made of wire, while the others were given surrogates made of cloth. Both groups had major developmental and psychological problems, but the babies with wire “mothers” were far worse off.

That means Pika, who has already been stolen from his mother and forced to endure physical cruelties just weeks after his birth, has also been deprived of something intangible, something so important that it will have an indelible impact on his life.

That is why when you see pet monkeys, you always see them clinging desperately to stuffed animals. The stuffed animals and blankets aren’t their “lovies” like a child would have. It’s much sadder than that. Those inanimate objects are their surrogate mothers which they turn to for comfort and a crude approximation of what it feels like to hold onto their moms.

Some “owners” don’t like that, so they place babies like Pika in barren cages. No matter how horrifically they abuse the babies, when the “owners” let them out in the morning the first thing the baby does is cling to his abuser. That is his nature.

So what happens to Pika?

There’s a timer on cuteness. Pika will be an adorable baby for about a year, which will fly by. By that time he’ll already be showing signs of extreme discontent. He’s got no mother, no friends to play with, no troop, no one to groom or to groom him. He won’t be allowed to climb and explore like he would in the wild, nor can he forage. Food is something placed before him, not something he finds and picks from trees.

Pika, hardwired by hundreds of thousands of years of genetic heritage, will know something’s missing, but he won’t know why. He’ll start to “act out,” only he won’t think of it as acting out because he does not, and cannot, understand human social etiquette, nor what it means to keep things clean by human standards.

As he acts out, he’ll be punished, often severely. He’ll become more of a problem until at about 18 months his “owner” will get rid of him. Some people will take their pet monkeys to sanctuaries, but those are few and far between in China, spots are very hard to get, and the owner will be on the hook for monthly payments for as long as Pika lives, which could be up to 25 years.

So it’s more likely that Pika will be poisoned or simply dropped off somewhere in the woods far from home where he’ll starve or be killed, because he doesn’t have the skills to survive and his kind live in troops. If he’s dropped off where there are other monkeys his chances will be even more slim, since macaques will not accept troop outsiders and can get violent if they perceive an interloper in their territory.

As for Pika’s owner, if she’s not tired of the whole business she’ll buy a new baby. Some women are one and done, but others see it as practicing for parenthood and/or they enjoy the dopamine rush of online attention and praise. I’ve seen some Chinese women go through half a dozen babies, often buying two or three at a time so they can stage spectacularly cruel contests, like dropping a single bottle into a cage and filming the babies fight over it.

What I’ve written here doesn’t even scratch the surface of the cruelty involved with the baby monkey “pet” fad, but don’t make the mistake of believing this is a thing that only happens in China, Thailand or Cambodia. Some 15,000 baby monkeys are purchased every year by Americans, who fare no better when it comes to reaching that 18-to-24-month point when formerly cute, docile babies grow into resentful, frustrated juveniles and become destructive.

While sanctuaries like Jungle Friends exist, they are overcrowded and the same challenges apply to American monkey “owners” as they do to their Chinese counterparts.

We’ll revisit this whole nasty business in a future post, but in the meantime, I ask you to question “cute” animal videos, especially where wild animals and humans are involved.

A note about Youtube and Google: Youtube is owned by Google, whose founders often bragged about their motto: “Don’t be evil.” Youtube and its content moderation teams are well aware their platform hosts tens of thousands of animal abuse videos, including innumerable videos of monkeys — often babies — being abused in horrific ways. There are entire channels, monetized and in good standing with Youtube, that cater exclusively to a depraved audience of self-described monkey haters who call infant macaques and other monkeys “tree rats” and not only provide steady advertising income to the channel operators — which can be life-changing money in countries like Vietnam and Cambodia — but send money via PayPal and Venmo to them with requests for specific kinds of torture.

Youtube has been aware of this for almost a decade at least. Going back to 2014, I was one of a group of dozens who mass reported channels to Youtube, tagging blatant and horrific animal abuse. Every report was ignored. The only thing that prompted Youtube to action was when I contacted a friend who worked for PETA at the time and got them to pressure Youtube directly to take down a handful of notorious monkey abuse channels. Youtube took action, but those channels were quickly replaced by new ones, creating a game of wack-a-mole.

To this day, and despite steady pressure and negative coverage in the press, Youtube takes little more than symbolic action on animal abuse videos, particularly those involving monkeys.