There’s a scene in the film adaptation of Stephen King’s Doctor Sleep that shows Ewan McGregor’s character, Danny Torrance, working the night shift as a hospice orderly when a cat jumps up onto the desk and nuzzles his hand.

“Hi, Azzie,” Torrance says, and watches as the cute feline pads down the hall and enters a patient’s room.

When Danny pokes his head in, the patient is distraught. He knows he’s going to die.

“Cat’s on the bed,” the man says. “I knew he would be. That cat…always seems to know when it’s time. Guess it’s time.”

Danny shakes his head.

“No,” he reassures the old man. “It’s just Azrael being a silly

old cat.”

“Nope. Been that way since I got here. The cat knows when it’s time

to go to sleep, everybody knows that. I’m gonna die.”

It’s a pivotal moment early in the movie because it marks Danny’s evolution into Doctor Sleep, a man whose innate ability to “shine” allows him to comfort the dying. (Yes, Doctor Sleep is the sequel to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Do yourself a favor and watch the Director’s Cut, which is the definitive and most satisfying version. It’s a long film, but worth it in every sense.)

It turns out Azzie is based on a real cat: Oscar, the resident feline at Steere House Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Providence, Rhode Island.

Oscar, who died in 2022 at the age of 17, had an uncanny ability to sense the imminent deaths of patients. When someone was near death, Oscar would leap onto the person’s bed and stay with them until they passed.

When his story was first publicized in a 2007 essay in the New England Journal of Medicine, Oscar had “predicted” the deaths of a few dozen patients.

“Thus far, he has presided over the deaths of more than 25 residents on the third floor of Steere House Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Providence, Rhode Island. His mere presence at the bedside is viewed by physicians and nursing home staff as an almost absolute indicator of impending death, allowing staff members to adequately notify families. Oscar has also provided companionship to those who would otherwise have died alone. For his work, he is highly regarded by the physicians and staff at Steere House and by the families of the residents whom he serves.”

In a follow-up story by Reuters in 2010, Oscar had snuggled with more than 50 dying patients.

To be clear, no one’s suggesting Oscar is peering into supernatural realms. Cats are known for their remarkable hearing, but they’ve also got an exceptional sense of smell. In fact, they have a unique olfactory organ in their mouths, the vomeronasal organ, that allows them to “taste” scents.

We know very little about what kind of information they’re able to glean from scent alone, but we do know animals can sense things that would otherwise require sophisticated machines for us to detect, including cancers and other diseases.

It may be that the most unusual thing about Oscar’s case is that he was allowed to live in a nursing home. The vast majority of medical facilities have strict prohibitions against allowing animals due to potential allergies and the perception that they’re dirty, despite the fact that they have significant therapeutic benefits. Even the facilities that do allow animals typically do so under controlled circumstances and for short periods, as when therapy dogs or cats are brought to visit patients.

Perhaps we’d hear about Oscars all the time if they were resident cats in hospitals and nursing homes.

“I don’t think Oscar is that unique, but he is in a unique environment,” Dr. David Dosa told Reuters. “Animals are remarkable in their ability to see things we don’t, be it the dog that sniffs out cancer or the fish that predicts earthquakes. Animals know when they are needed.”

It’s a reminder that just because we can’t see, smell or hear something, that doesn’t mean there’s nothing there. When dogs “bark at nothing,” they may have caught the scent of a stranger in the neighborhood. When a cat stares at a wall, it could be picking up mice making sounds that are too high in frequency for human ears to detect.

There are likely thousands of sounds, smells and even forms of tactile feedback to which we remain oblivious, but are noticed by animals. Migratory birds, for example, have magnetoreception abilities. That is to say, they can detect Earth’s magnetic field and magnetic dips, an ability they put to use when navigating as the seasons shift.

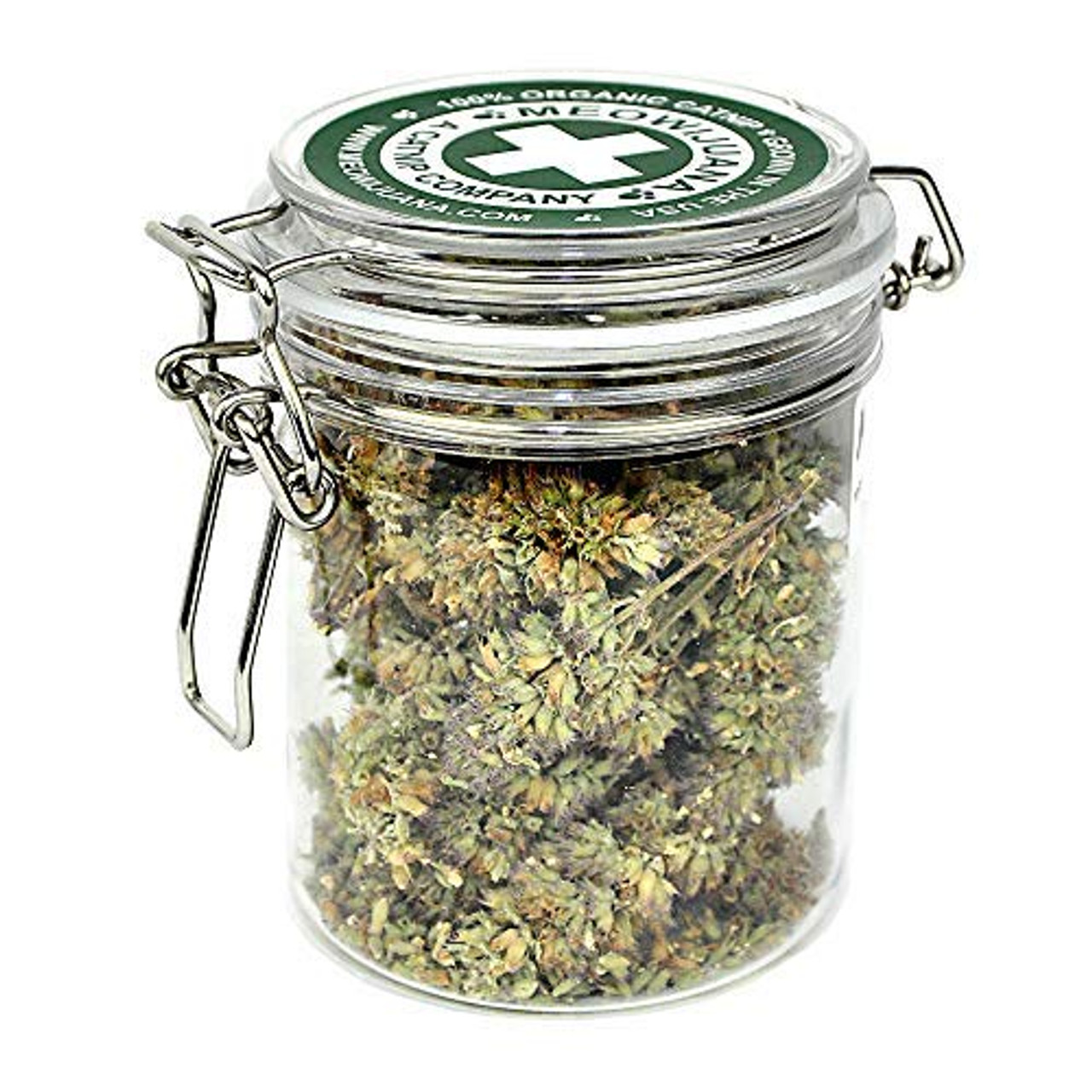

And then, of course, there’s Buddy and his incredible ability to detect catnip. Little man could be in a deep sleep in another room, yet the instant I open the sealed container of the good stuff, it’s a matter of seconds before he’s at my feet, meowing happily. In fact, it’s a reliable way to find him when he’s in some novel hidden napping spot, doesn’t respond to me calling for him, and I get worried because I haven’t seen or heard him in some time.

So next time your cat freaks you out by apparently staring at a corner of your living room, remind yourself she’s probably been alerted to something you can’t sense — and be wary of any cats who aren’t snugglers but suddenly climb into your bed.