You read that right. According to a survey of more than 2,000 people from an independent industry research firm, 51.7 percent of American adults did not read a book in 2021.

More than one fifth (22.01 percent) haven’t read a book in three years, and more than 10 percent haven’t read a book in 10 years.

There are obvious reasons for that, including the choice of many other mediums for entertainment, plus an unprecedented volume of content offerings from streaming networks and traditional TV, meaning most of us have tens of thousands of movies at our fingertips through paid subscriptions like Netflix, Amazon and Hulu, as well as free ad-supported streamers like Tubi and the Roku channel.

Then there’s internet doomscrolling, the endless consumption of news (of which I am guilty), social media platforms designed to keep people engaged, fan fiction sites and a million other leisure activities competing for our attention.

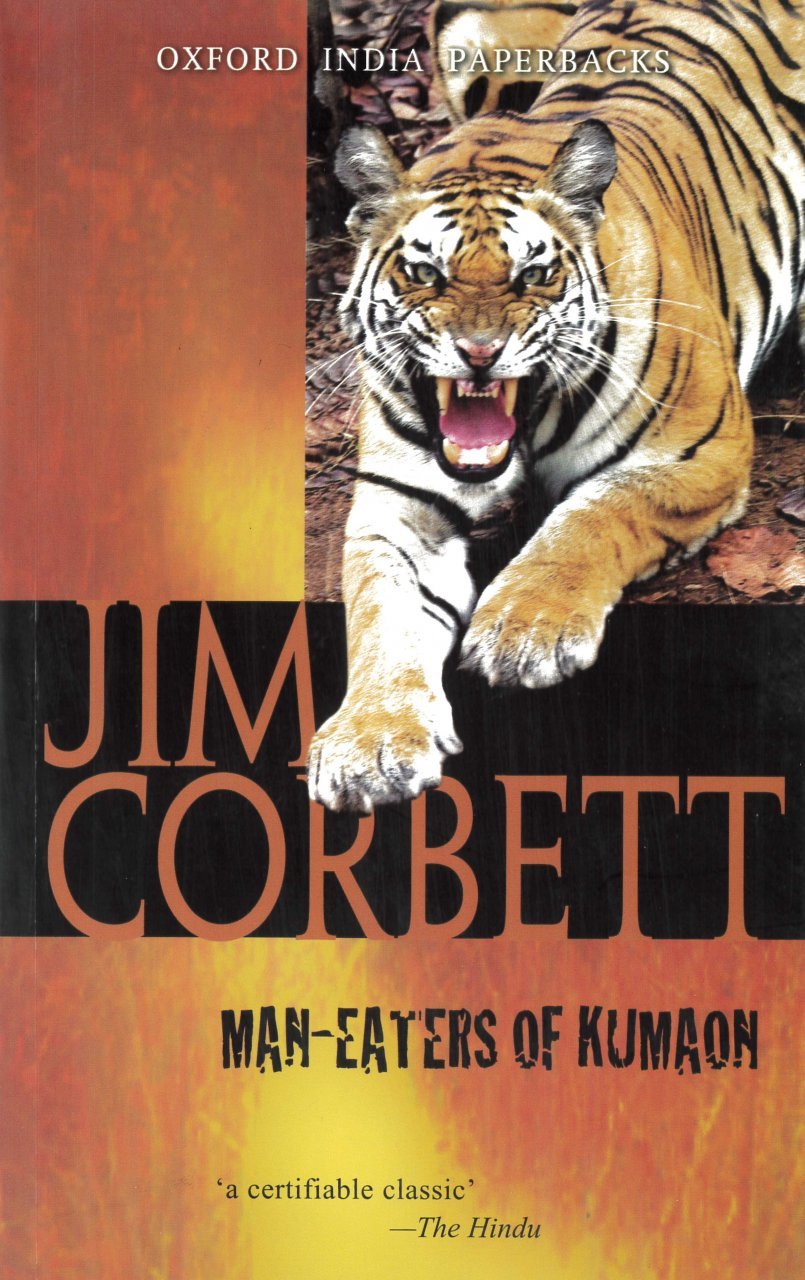

Yet none of those things have a quality that books do. When you read a book, you are entering a theater of the mind created by one mind. Not a movie that has 500 crew members in addition to its cast, focus groups, script writers, script doctors and script polishers. Not a TV show written by committee in a writers room to the specifications of network honchos. With a fiction book, you’re allowing one person’s imagination to usher you into a story, trusting in their storytelling skill to make the experience worthwhile. With a well-researched non-fiction book, you can travel back in time, reliving wars, coups and personal stories, events that shaped the world and events that meant the world to a few people.

Not surprisingly, the survey shows, the percentage of people who read books regularly is lower for younger age cohorts. Credit YA fiction, like Harry Potter, The Hunger Games and similar series for turning at least some of them into readers.

The publishing industry is in a sorry state. In lean times publishers and their imprints have become as risk-averse as major movie studios, so they’re far less likely to take chances on new authors with new perspectives than they are to fall back on the same handful of big-name novelists or surefire memoirs like Prince Harry’s Spare.

Because of that, publishing houses don’t invest in developing younger up-and-coming writers the way they once did, and there are fewer literary journals and genre magazines for new authors to use as stepping stones.

Compounding the problem is the echo chamber in publishing: Because many publishing jobs offer low salaries, most of the people who can afford to take those jobs are independently wealthy, increasingly concentrated in places like Brooklyn, and share similar perspectives. That has a pronounced effect on the kind of books they’re publishing.

Still, I think we all share in the blame. I read only 12 or 13 books in the past year. That seemed low but not so bad until I though about it. That’s a measly 120 books in 10 years. It doesn’t add up to much over a lifetime.

When you put it like that, you either want to make sure every book you read is a gem, or you get your ass in gear, put down the junk news articles and smartphone, and dive into more books.

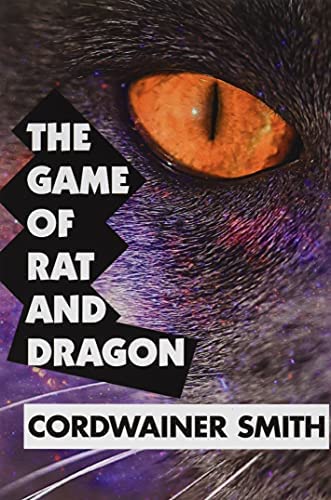

I am a science fiction junkie and wanted to read more female authors since my favorites happen to be a bunch of British guys — Iain M. Banks, Alastair Reynolds, Peter F. Hamilton — and managed a measly one fiction book by a female author in the past year, although it was pretty awesome. (Dead Silence by S.A. Barnes, also known as Stacey Kincade. I think she’s Barnes for science fiction and Kincade for other stuff.) I’ll definitely be down for the planned sequel, and I have Ursula LeGuin in the queue.

What are your reading habits? How many books do you read per year, and are you happy with your pace?