Pet site listicles name the Ashera cat as “luxurious,” one of the most expensive and rare breeds ever. Videos show surprisingly large, exotic-looking felines with leopard-like rosettes and a calm demeanor.

In media reports a man named Simon Brodie talks the breed up, presenting himself as the CEO of a biotechnology company that “developed” the Ashera through careful genetic manipulation, selecting only the most positive traits. For a few thousand dollars more, Brodie promises, they come in hypoallergenic versions too.

Brodie often sounded like he was describing the newest iteration of a tech product rather than a cat, calling the Ashera “a status symbol” and listing its optional features the way a car salesman talks about leather and heated seats.

“It’s exotic, but under the skin it’s a domestic house cat, very easy to take care of and extremely friendly,” he told Reuters. “Everybody has thought at one time, wouldn’t it be great to have a leopard at home, or a tiger? Obviously, you can’t and this is about the nearest thing to it.”

Brodie conjured images of engineers poring over genetic data and working with gene-editing equipment in a laboratory to create the perfect pet.

“Anybody can throw the ingredients in, but unless you know what ingredients are the best ingredients in the best percentages, you’re not going to produce the same final product,” Brodie told the U.K. wire service.

The problem? The Ashera doesn’t actually exist, and there’s no evidence Brodie has ever been in a lab, let alone spearheaded the creation of a new breed of feline.

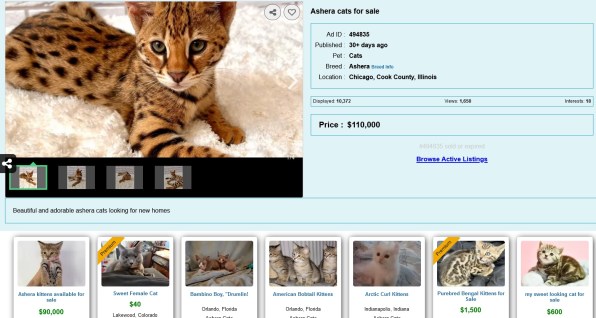

Sadly, people might not realize that right away because of the publish-now, verify-never nature of web publications. Catster maintains a current page for the “breed,” citing its “outstanding lineage” and its supposed status as “one of the rarest and most expensive cats in the world,” potentially setting back its owners $100,000 or more per cat. You have to scroll down before the site warns about the “controversy and skepticism regarding the breed’s origins,” as if there’s still a debate whether the Ashera is a real breed.

Sites I’d rather not link to include the Ashera in their lists of “most exclusive” and “rare” breeds, and recent Reddit threads claim their price owes partly to their rarity because the company “only breeds about 100 cats a year.” When’s the last time you heard cats didn’t breed enough?

There are even “Ashera cat communities” designed to make it look like there are large online groups of happy owners, and Youtube channels featuring videos of Savannahs labeled as Asheras.

A sketchy operation

But dig a little deeper and you’ll find the truth. The Savannah Cat Association calls the Ashera a hoax, says the cats are Savannahs with fancy marketing, and details experiences people have allegedly had with Brodie. His company appeared to be a one-man operation with a voice mailbox, and people who purchased the pets said they were told to wire down payments to an account in the United Arab Emirates.

There are even claims Brodie was drop-shipping the cats, with customers saying they were delivered directly from an Oklahoma breeder of Savannahs.

And the people who saw an opportunity to have a pet cat despite severe allergies? They weren’t happy either, even those who negotiated deep “discounts” with Brodie.

“I don’t think any cat is worth $4,000,” a customer named Mike Sela told Columbia Journalism review, “but this seemed like a magical opportunity, especially with parents trying to get something for kids. You never thought you could get a cat and this is your chance.”

A group of angry customers who were promised hypoallergenic pets contacted ABC News, whose Lookout team enlisted the help of a biotechnology company to test cats purchased from Allerca, Brodie’s company. The tests showed the Ashera cats had the same amount of Fel d 1, the primary allergen in feline saliva, as the typical cat and could find no evidence of Brodie’s claims that he’d engineered an exotic cat sans allergens.

CJR took mainstream and legacy press outlets to task for reporting uncritically on Brodie’s claims despite the lack of any documentation, peer-review studies proving gene-edited hypoallergenic cats are possible, and for a complete lack of due diligence on the man himself. Per CJR:

“What Time, National Geographic, and other major outlets, including The New York Times, missed was that Brodie has no background in genetics—but he does have a well-recorded background in running scams. He was arrested in England, his native country, for selling shares in a non-existent hot-air balloon company. In the United States, he has left a wake of evictions, unpaid loans, and suits by unpaid employees. One judgment against him that stands out is by a company called Felix Pets, founded about a year before Allerca with the same goal of breeding hypoallergenic cats by eliminating the Fel-D-1 gene.”

Indeed, as the complaints piled up and Brodie’s deceptions began to catch up with him, the San Diego Union Tribune reported Allerca had been evicted from its “offices” — Brodie’s home address.

News stories say Brodie has changed his name numerous times and if he’s still out there, he’s almost certainly not Simon Brodie anymore. But the Ashera cat scam isn’t dead.

We found dozens of sites offering “Ashera kittens,” and online marketplaces for animals still have regularly-updated listings from people claiming they’re selling “genuine” Ashera cats in 2024. There’s also at least one group claiming they’re “officially licensed Ashera cat breeders,” touting a lofty “mission” not only of providing cats for people with allergies, but also “preserving exotic wildlife.”

The myth of hypoallergenic cats

Although there have been recent efforts to neutralize Fel d 1, they come from actual scientists who have published their work for peer review, or from public pet food companies that have paired with scientists to create kibble they claim reduces the Fel d 1 allergen in cats who eat it. They’re also focused on attacking the protein, not breeding or creating cats that lack it in the first place.

People with allergies should understand that despite what they may read online, hypoallergenic cats do not exist. No one has been able to “engineer” a feline without the Fel d 1 protein.

There’s serious debate among geneticists about whether trying it is ethical, as no one knows exactly what function Fel d 1 serves or what the potential consequences may be for editing it out of feline genetic code.

So if you’re looking for a “luxury cat” or you just want a cat that won’t trigger your allergies, beware before you’re separated from your hard-earned cash. As always, if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.