A California biologist who shot and killed 13 cats as part of a “predator management program” referred to the felines’ corpses as “party favors” in a celebratory email to colleagues, according to a copy of the email.

David “Doc Quack” Riensche, a senior wildlife biologist with California’s East Bay Regional Park District (EBRPD), used a 12-gauge shotgun under cover of night to shoot the cats, documents obtained from the EBRPD show.

Riensche and EBRPD knew the felines were part of a colony near Oakland Coliseum managed by Cecelia Theis, a local woman who provided them with veterinary care, food, water and conducted TNR (trap, neuter, return) services to prevent the colony’s population from growing.

They did not warn Theis that they were going to cull the colony late last year, nor did they reach out to contacts in the area’s extensive local shelter and rescue network to trap and remove the strays, despite repeatedly stating that shooting cats is an absolute “last resort.”

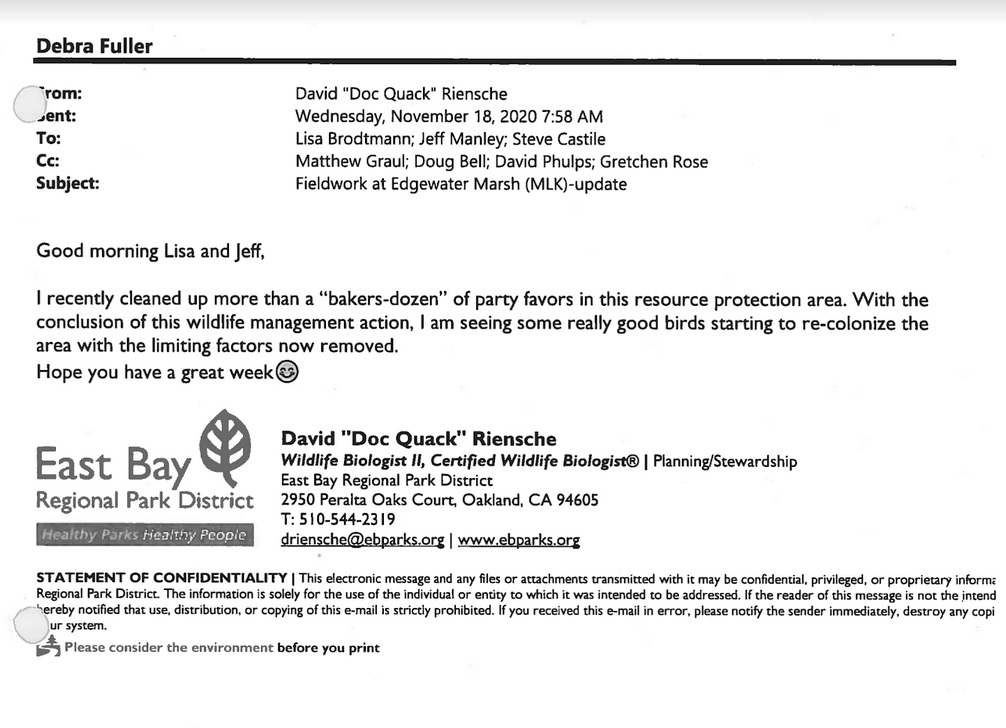

“Good morning Lisa and Jeff,” the email from Riensche reads, dated Nov. 18, 2020. “I recently cleaned up more than a ‘bakers dozen’ of party favors in this resource protection area. With the conclusion of this wildlife management action, I am seeing some really good birds starting to re-colonize the area with the limiting factors now removed. Have a great week.”

Riensche, who disposed of the dead cats in trash bags that he tossed into a bin, signed off the email about the dead cats with a smiling emoji.

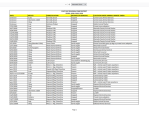

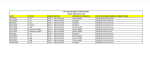

Although Riensche uses coded language in the email, the district’s own records, Riensche’s overtime statements for overnight hours, timestamped audio of dispatch calls and EBRPD’s own timeline of the cat killings all line up with the date of Riensche’s email and a spreadsheet documenting when and where Riensche shot the colony cats.

Tiffany Ashbaker, a volunteer with Alameda’s Island Cat Resource and Adoption, said she was horrified when she read Riensche’s email describing the dead cats as “party favors.”

“I was disgusted. Way beyond hurt,” said Ashbaker, who helped Theis trap, neuter, vaccinate and relocate the Oakland colony cats. “I find this to be unethical and he should be removed from his position at EBRPD because of it. I understand why we should try to have cats further away from the protected areas, but how they handled this was eye opening for sure.”

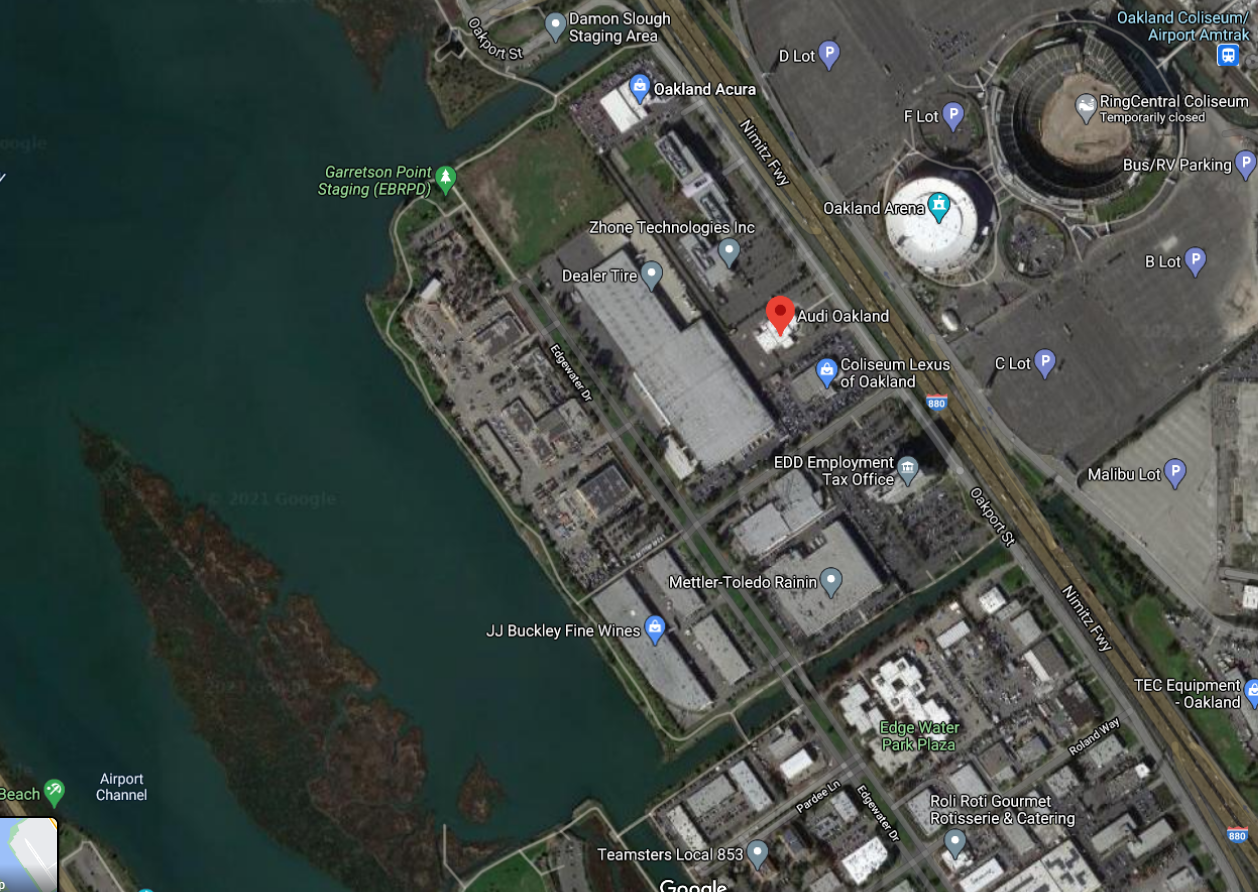

The cats lived between two auto dealerships in an industrial area separate from the MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline, a park in Oakland managed by the EBRPD. When Theis returned to the area to feed the cats on Nov. 3 2020, she realized several were missing. Over the following days more cats began to disappear, Theis and Ashbaker noted.

When Theis asked EBRPD about the whereabouts of the colony cats, a district staffer told her EBRPD wasn’t involved and didn’t remove any cats. EBRPD then amended its response, saying it had trapped the cats and brought them to local shelters.

But none of the local shelters had any records of taking cats from EBRPD, nor did they have the missing cats in their care.

EBRPD admits its biologist killed colony cats

Theis went to KGO, a local ABC News affiliate, and when a reporter began asking questions about the missing cats, a spokesman for the district finally admitted one of its employees — later identified in documents as Riensche — had shot the cats as part of the “predator management program.”

Theis said she felt “a horrible feeling in my gut” when she realized why the usually friendly strays and former pets of the colony were suddenly skittish. Riensche shot the colony cats over a series of nights, returning to the park in the late hours with a shotgun to kill two or three at a time.

Theis said she now understands why the remaining cats were so fearful and skittish when she came by for their regular feedings. One cat named Sherbert jumped on her car hood, and two others meowed insistently at Theis, “trying to tell me.”

“I feel this horrific feeling that they went through terror and were trying to tell me,” Their said. “They weren’t eating like they did usually.”

Some EBRPD board members have expressed sympathy for what happened, Theis said, but she described being “depressed” and worried because the district won’t give her any guarantees that it won’t kill more cats.

“We feel horrible about this, you know, this is really one thing that’s just really sad,” Matt Graul, the EBRPD’s chief of stewardship, told KGO in December, after the public first learned the cats had been shot.

Despite that, EBRPD ignored public records requests from the TV news station, and a spokesman for the district defended the cat culling, saying it was necessary to protect endangered birds who winter in the nearby marshlands.

Stray and feral cats “are not part of a healthy eco-system” EBRPD spokesman Dave Mason said, claiming his agency was protecting endangered wildlife in the area.

Public and animal rights groups demand an end to cat killing practice

After intense public backlash, including a petition with 70,000 signatures protesting EBRPD’s actions, several district board members were quoted in media reports saying they would end the practice of killing cats and would demand an investigation. Almost five months later, the district is instead moving ahead with a plan to contract cat-killing (and the culling of other animals like foxes and opossums) to a federal agency, and there has been no investigation.

Ashbaker, Theis, the non-profits In Defense of Animals and Alley Cat Allies, and local shelters have all demanded EBRPD stop killing animals entirely. District officials continue to argue it’s necessary to protect endangered birds, despite a lack of scientific evidence supporting the idea that arbitrarily shooting animals has any measurable impact on bird populations.

EBRPD has made one concession: It’s promised to reach out to rescues and shelters in the area for help removing cats before making the decision to deal with them lethally.

“While we’re pleased that the policy seems to be to work with local advocates as to prefer not to killing cats, we want to see a pledge that this never happens, ever again,” Fleur Dawes of In Defense of Animals said in February.

The district “should have been up front from the beginning, saying ‘This wasn’t what should have happened, [so] let’s make it right,'” Ashbaker said.

EBRPD has been unable to provide proof that the cats were killing birds on the marsh or that Riensche shot the cats on district property.

In response to a public records request for any documentation of cats preying on birds in the marshlands, EBRPD produced a single document from 1992, noting one incident with one cat about 35 miles south of the MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline where Riensche shot 13 cats in late 2020. During a survey some time before 1992, an EBRPD employee saw an example of “[California Clapper] rail predation” by “what we determined was a feral cat, in a marsh in the East Palo Alto area,” where it says “many cats are found.” The document mentions another cat that was sighted swimming “in flooded tidal salt marshes” in south San Francisco Bay, likely “foraging” for an endangered mouse species.

The district has not been able to produce any written guidelines or protocols describing how its employees determine if a cat should be shot instead of being relocated or brought to a local shelter, except for a vague summary of minutes from a 1998 meeting during which they claim the policy was approved.

EBRPD has been unable to produce copies of the cat-killing policy itself, despite several public records requests seeking that document.

In addition, in internal emails after a KGO reporter began asking questions about the cat killings, several EBRPD staffers questioned whether they have any documentation saying cat culling is an acceptable policy.

EBRPD internal discussion: Are we following our own rules?

In those same internal emails, which were obtained from EBRPD via public records requests, staffers wondered if the district was following its own rules requiring it to reach out to local shelter networks and receive approval from federal authorities to kill cats. One EBRPD official, assistant general manager of public affairs Carol Johnson, noted the document EBRPD used as justification “does not mention dispatching these animals,” and requires the district to “work with animal rescue organizations to help trap feral cats.”

“[The] question is, are we following the protocols listed in the document?” Johnson asked her colleagues in a Dec. 2 email. “I would argue we are minimally following through with the organizations and we have nothing to say lethal means is acceptable.”

Internal correspondence among EBRPD staff, obtained via a public records request, show worried staffers searched in vain for a written policy on killing cats before using a Google search to find another agency’s policy.

EBRPD finally produced a copy of minutes from a 1998 meeting with notes attached saying the cat-culling policy had been approved by the board, but if a copy of the policy exists, the district has been unable to produce it.

In December Mason said cats were only shot as a last resort and “[L]ethal removal only happens when feral cats are in the act of hunting wildlife on District property,” but none of the documents say the cats Riensche shot were hunting. Indeed, it would require an extraordinary stroke of luck for the biologist to find 13 cats preying on endangered birds in just a few nights.

Despite public records requests, the EBRPD was unable to provide proof that Riensche had consulted anyone before shooting the cats. Records indicate no one was notified until after Riensche killed the animals.

In addition, the cat colony sat some distance from the protected marshland: An office park, electric car charging station, at least three parking lots and a substantial body of water are between the cat colony’s home and the marshland. That’s a distance considerably longer than most stray and feral cats range from their homes, and domestic cats are notoriously averse to water or getting themselves wet.

Records line up with cat shootings

While Riensche uses coded language by referring to the cats he shot as “party favors” in his email to colleagues, it was sent on Nov. 18, the day after EBRPD’s own records show he killed the last of the colony cats. Internal documents from the EBRPD, obtained through public records requests, as well as the district’s own public timeline of events, show the dates the cats were killed line up with Riensche’s email. In addition, in audio recordings of his radio contact, Riensche advises dispatchers only after he’s fired the killing shots.

“Yeah this is Dave Riensche in wildlife at MLK, I just dispatched an animal down here, so if you get a call, it was me,” Riensche tells a dispatcher in one of the calls on Nov. 13 at 6:24 a.m.

EBRPD’s records show the only animals killed on that day were cats.

(Click the embedded audio to hear Riensche call dispatch on Nov. 13, 2020.)

Finally, according to EBRPD’s records, Riensche received overtime for working on nights that correspond to the same dates EBRPD says the cats were shot. [EBRPD document: TIMECARDS (REDACTED)]

Riensche, who has been employed as a biologist with the district for decades, is a prominent birder whose work involves protecting birds and other endangered species from predators wild and domestic. He penned a newsletter, Bird News, in the early aughts and is on record saying there’s “a wealth of evidence” that stray and feral cats are the primary danger to bird populations.

Shooting cats as a ‘first resort’

Riensche earned $182,951 in salary and benefits in 2019, the most recent year for which salary data is available for public employees in California. Riensche earned a base salary of $90,239 and $56,050 in overtime, including for overnight hours spent shooting animals in EBRPD’s parks.

An Oakland woman who wrote to the EBRPD after the district came clean about the cat killings related an anecdote about Riensche from 2019.

The woman worked with a local rescue that received a call from a parks employee who wanted help trapping and relocating a female cat and her young kittens who were living on or near an EBRPD park. The rescue volunteers were working with the EBRPD employee, making plans for the cat and her babies to be vaccinated and spayed/neutered, and even had homes lined up for some of the kittens, the woman wrote in a Nov. 25 email.

After visitors to the park saw the mother carrying a dead rabbit back to her kittens, “Doc Quack [Riensche] then reportedly told employees he was going to shoot the cats,” the volunteer wrote.

The mother cat “disappeared” and her fate was unknown, but the rescue was able to work with the EBRPD employees to get the kittens trapped. However, Riensche wasn’t happy with that outcome, she wrote.

“I was told later by an employee, that they were reprimanded for saving the cats and going outside of the EB Parks, to get this help,” the woman wrote in her letter to EBRPD. “Apparently, they should have just been quiet and let Doc Quack shoot the cat family.”

The connection between birders and cat killing

Cat killing isn’t unusual among birders. In 2007 a Texas man named James M. Stevenson — founder of the Galveston Ornithological Society — admitted killing dozens of cats on private and public property after coming to believe the cats were killing piping plovers, shorebirds who commonly nested in the area.

An article in the Los Angeles Times noted Stevenson wasn’t coy about what he’d been doing:

In a 1999 posting on an Internet bulletin board for bird lovers, Stevenson nonchalantly described killing many feral cats during his first year living on Galveston Island. He rationalized his acts as a way to restore the natural order.

“I’m sorry if this offends — but I sighted in my .22 rifle, and killed about two dozen cats,” Stevenson wrote in his message, titled “killer kitties; kittie killers.”

“This man has dedicated his whole life to birds,” Stevenson’s attorney said in his defense. The case ended in a mistrial.

In 2011, a wildlife biologist employed by the Smithsonian National Zoo’s Migratory Bird Center was found guilty of animal cruelty “for sprinkling poison atop cat food intended for feral cats living in Washington, DC.”

Nico Arcilla, then known as Nico Dauphiné, was well known as a birder and outspoken critic of cats. A group of people who cared for strays near Washington’s Meridian Hill Park contacted the Humane Society after noticing food they left out for the cats “would sometimes become covered by a white powdery substance overnight.”

After the Humane Society and Washington police tested the substance and verified it was poison, they set up a stakeout and had cameras trained on the food bowls. Footage, which prosecutors later exhibited on trial, was damning:

“Dauphiné [Arcilla] can be seen approaching the bowl, pulling something out of a small bag, reaching down toward the food twice, and then leaving the scene,” a sciencemag.org report reads. “The next morning, police found the food covered with the same white powder as before, which tested positive as poison.”

[Click here to see video of Arcilla poisoning the cat food.]

Arcilla wasn’t just a prominent birder and anti-cat campaigner — she is a co-author of several frequently-cited studies claiming cats kill billions of birds in the US each year. Those studies, which have been used to justify cat-culling policies around the world, are highly controversial, with critics blasting them for poor methodology, a lack of hard data, and arbitrary numbers plugged in to estimate both the national cat population and the felines’ impact on birds. For example, the authors estimate a national stray and feral cat population between 25 and 125 million, an estimate so vague that any extrapolations based on those numbers are virtually useless.

Riensche has repeatedly cited Arcilla’s work in public and private documents arguing that cats are primarily responsible for declines in bird populations.