The last decade has seen something of a renaissance in cat-related research, with insightful studies about feline behavior coming from researchers in the US and Japan.

On the other hand there’s been a glut of research into feline predatory impact and public policy, and the majority of those studies have been deeply flawed. They’re based on suspect data and tainted by the interests of people who are more interested in blaming cats for killing birds than they are in learning about the real impact of domestic felines on local wildlife.

Those studies have all taken extreme shortcuts — using data that was collected for entirely different studies, for example, or handing out questionnaires that at best lead to highly subjective and speculative “data” on how cats affect the environment.

Several widely-cited studies that put the blame on cats for the extirpation of bird species have relied on wild guesses about the cat population in the US, estimating there are between 20 million and 120 million free-roaming domestic cats in the country. If you’re wondering how scientists can offer meaningful conclusions about the impact of cats when even they admit they could be off by 100 million, you’re not alone.

No one had ever actually counted the number of cats in a location, much less come close to a real figure — until now.

When leaders in Washington, D.C., set out to tackle the feral cat problem in their city, they knew they couldn’t effectively deal with the problem unless they knew its scope. They turned to the University of Maryland for help, which led to the D.C. Cat Count, a three-year undertaking to get an accurate census with the help of interested groups like the Humane Society and the Smithsonian.

The researchers approached each of their local shelters and rescues for data, then assembled a meticulous household survey to get a handle on how many pet cats live in the city, and how many have access to the outdoors.

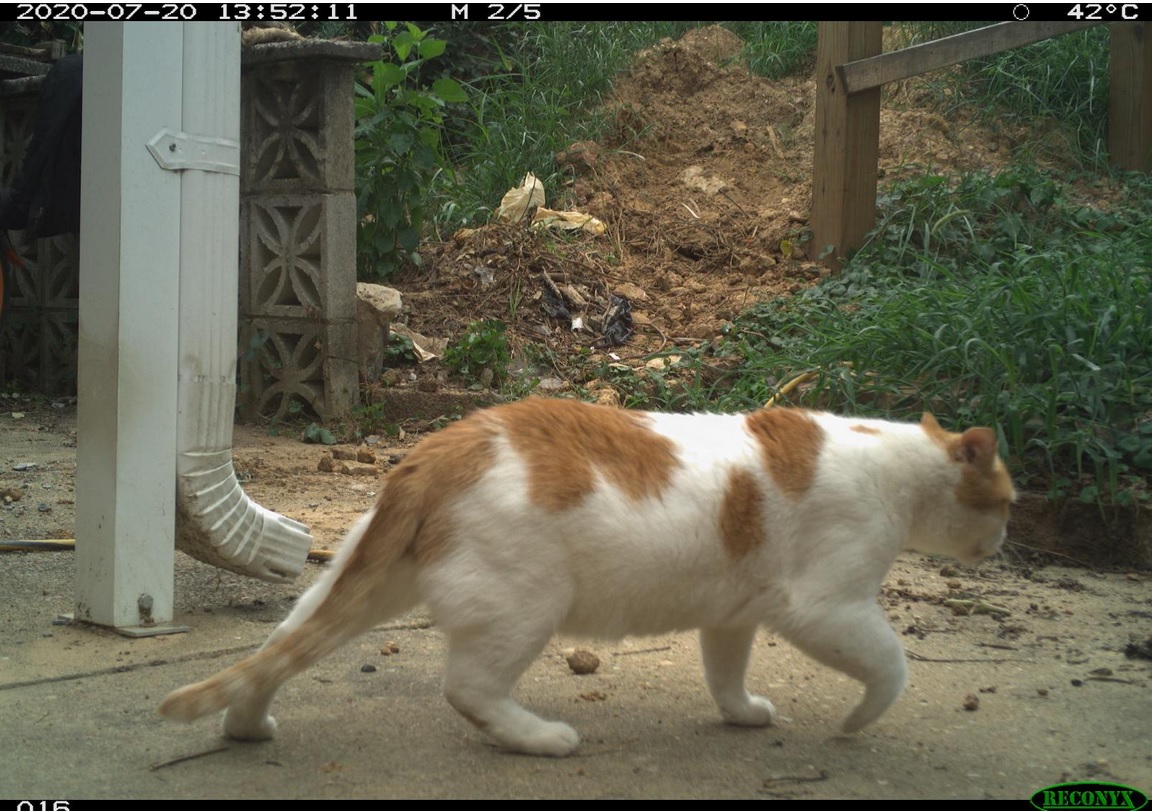

Finally — and most critically — they used 1,530 motion-activated cameras, which took a combined 6 million photos in parks, alleys, public spaces, streets and outdoor areas of private residences. They also developed methods for filtering out multiple images of individual cats, as well as other wildlife. And to supplement the data, team members patrolled 337 miles of paths and roads in a “transect count” to verify camera-derived data and collect additional information, like changes in the way local cats move through neighborhoods.

Now that all the data’s been collected and analyzed, the D.C. Cat Count finally has a figure: There are about 200,000 cats in the city, according to the study.

Of those, 98.5 percent — or some 197,000 kitties — are either pets or are under some form of human care and protection, whether they’re just fed by people or they’re given food, outdoor shelter and TNR.

“Some people may look at our estimate and say, oh, well, you know, you’re not 100% certain that it’s exactly 200,000 cats,” Tyler Flockhart, a population ecologist who worked on the count, told DCist. “But what we can say is that we are very confident that the number of cats is about 200,000 in Washington, D.C.”

The study represents the most complete and accurate census of the local cat population in any US city to date, and the team behind it is sharing its methods so other cities can conduct their own accurate counts. (They’ll also need money: While the D.C. Cat Count relied on help from volunteers and local non-profits it was still a huge project involving a large team of pros, and it cost the city $1.5 million.)

By doing things the hard way — and the right way — D.C. is also the first American city to make truly informed choices on how to manage its feline population. No matter what happens from here, one thing’s certain — the city’s leaders will be guided by accurate data and not creating policy based on ignorance and hysteria painting cats as furry little boogeymen.